/ News Posts / Making Music for People, Not Just for Peers

Making Music for People, Not Just for Peers

A Case for Audience-First Composition

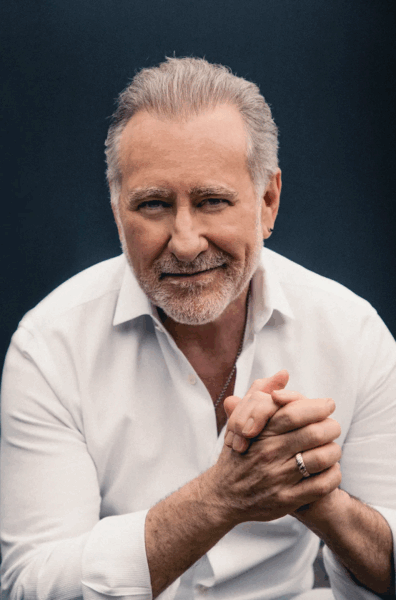

By NAfME Member José Valentino Ruiz, Ph.D. and Brian Bromberg,

GRAMMY®-Nominated Bassist-Producer-Composer

In jazz education and professional music circles, technical mastery is often the measuring stick by which musicians are judged. But what if we’ve been measuring the wrong thing? What if the most impactful music isn’t what impresses our peers, but what moves our listeners?

This was the underlying tension in a wide-ranging conversation with Grammy®-nominated contemporary jazz bassist, composer, and producer Brian Bromberg, whose career spans decades of recording, touring, and producing across genres. “Nobody walks down the street singing a solo,” Bromberg said. “They think of the melody. The song that sticks in their head—that’s it.” This observation isn’t just a poetic truth; it’s a challenge to musicians, educators, and producers alike: Are we writing and performing in a way that people can carry with them?

The Virtuosity Trap

It’s not that technical brilliance doesn’t matter. It’s that brilliance is often misapplied. Bromberg, reflecting on his own work, put it bluntly: “You play for the music, not for yourself . . . My job is to make that bottle of water refreshing.” In other words, virtuosity should serve the music — not overshadow it.

For many trained musicians, particularly those emerging from conservatory or academic jazz programs, the pressure to display chops often overshadows the mission to communicate. The result? Music that’s impressive but forgettable. Dense but emotionally opaque.

This dynamic is reinforced in education. Students are trained to master scales, modes, harmonic substitutions, and odd meters. But how often are they trained to ask: What does this music make someone feel? Or: What does this moment mean to the listener?

Bromberg has a clear philosophy: “If [the audience] can’t grab onto the melody and can’t grab onto the song, the solo is irrelevant . . . You have to honor the music first.” It’s a call to re-center the audience not as consumers, but as recipients of human connection.

From Albums to Fragments: The Attention Economy Shift

Bromberg also noted how listener behavior has changed in recent decades—from the ritual of listening to albums, to the fragmented, swipeable world of modern streaming culture. “Back in the days, you’d buy records, go to music stores, hang out. It was a community. Now it’s like—ping! Then you lose your attention and go to something else.”

We no longer live in a world that rewards long-form musical attention spans. The average listener hears your track in a playlist between two TikToks and a commercial. That doesn’t mean musicians should reduce their creativity. But it does mean they must become more intentional about how they connect.

This is where the craft of audience-first composition becomes an act of artistic generosity. It’s not about “dumbing down” the music—it’s about making sure the audience can find themselves in it.

Five Practical Approaches to Audience-First Music Making

These insights aren’t just philosophical. They’re teachable, practical, and applicable across genres. Here are five suggestions inspired by Bromberg’s reflections that musicians and educators can apply immediately.

-

Lead with Melody, Not Technique

Melody is the bridge between creator and listener. Bromberg insists: “If they can’t grab the melody, they can’t grab the music.” In practice, this means prioritizing melodic phrasing, hooks, and motifs over harmonic or rhythmic complexity—especially early in a piece.

- Try this: Assign students to write an 8-note melody and develop it into a short piece using only variation and emotional contrast, not complexity.

-

Clarify Emotional Intent

As Bromberg points out, “You want people to feel it—you want to move them.” But most music instruction focuses on form, not feeling. Ask: What emotion is this piece trying to evoke? Does the performance make that emotion legible?

- Try this: Ask students to title each section of their piece with one-word emotional descriptors (e.g., “longing,” “defiance,” “relief”). Have listeners guess and compare.

-

Say More with Less: Master Short Forms

Bromberg notes that “radio’s not going to play a six-and-a-half-minute song,” and that commercial formats demand tighter storytelling. This doesn’t mean compromising depth—it means embracing brevity as a creative challenge.

- Try this: Have students rework a five-minute piece into a compelling three-minute arrangement. What stays? What goes? What intensifies?

-

Workshop with Non-Musicians

“You don’t make records for bass players,” Bromberg says. “I make records for people.” Playing music for non-musicians can reveal what’s actually landing—and what’s not.

- Try this: Invite non-musicians to a critique session. Ask: What did you feel? What did you remember? What confused you? Make this part of the feedback loop.

-

Teach the Art of Delivery

“Delivery is the highest order,” Bromberg says. “Now you’re not just creating—you have to connect in real time.” In the streaming age, musicians must think like storytellers and strategists, not just performers.

- Try this: Every composition assignment should include a delivery plan: platform choice, caption copy, visual treatment, and timing. Help students bridge the gap between creation and communication.

Human First, Musician Second

At the heart of Bromberg’s reflections is a hierarchy that’s both humble and profound:

“Human first. Musician second. Bass player third.”

In a time when the music industry is increasingly data-driven, content-saturated, and image-obsessed, this hierarchy re-centers the practice of music in humanity. It reminds us that beyond the solos, beyond the harmonies, and beyond the gear, music is—and always has been—about people.

Educators and musicians alike must return to that truth. Not just to build fanbases or survive in the streaming economy, but to make music that matters—music that someone, somewhere, will carry with them long after the final note fades.

About the authors:

NAfME member Dr. José Valentino Ruiz, Associate Professor at the University of Florida’s (UF) School of Music, is a globally recognized musician, scholar, and arts entrepreneur, acclaimed for his multi-Latin GRAMMY®, EMMY®, and DownBeat® Award-winning contributions (55 awards) across performance, production, education, and digital media. As Founder and Director of UF’s Music Business & Entrepreneurship program, he teaches innovative courses and leads internationally impactful initiatives that integrate music, business, and social impact. A prolific artist and academic, he has authored more than 120 peer-reviewed publications, produced 150+ albums, and delivered more than 110 keynotes and workshops worldwide. Dr. Ruiz continues to shape the global creative industries through his leadership in music entrepreneurship, interdisciplinary research, and arts education.

NAfME member Dr. José Valentino Ruiz, Associate Professor at the University of Florida’s (UF) School of Music, is a globally recognized musician, scholar, and arts entrepreneur, acclaimed for his multi-Latin GRAMMY®, EMMY®, and DownBeat® Award-winning contributions (55 awards) across performance, production, education, and digital media. As Founder and Director of UF’s Music Business & Entrepreneurship program, he teaches innovative courses and leads internationally impactful initiatives that integrate music, business, and social impact. A prolific artist and academic, he has authored more than 120 peer-reviewed publications, produced 150+ albums, and delivered more than 110 keynotes and workshops worldwide. Dr. Ruiz continues to shape the global creative industries through his leadership in music entrepreneurship, interdisciplinary research, and arts education.

Brian Bromberg is a Grammy®-nominated virtuoso bassist, composer, and producer whose genre-defying career spans over four decades, pushing the boundaries of what the bass can do in jazz, fusion, funk, and beyond. From touring with Stan Getz at age 19 to releasing more than 20 acclaimed albums, Bromberg’s discography includes tributes to legends like Jaco Pastorius, Scott LaFaro, Jimi Hendrix, and Jobim, as well as original works that top jazz charts worldwide. His pioneering use of piccolo bass and genre-blending arrangements have earned him widespread acclaim, chart-topping success, and collaborations with hundreds of music icons. Whether producing intricate acoustic jazz trios or high-energy smooth jazz recordings, Bromberg continues to innovate, inspire, and elevate the art of bass playing.

Brian Bromberg is a Grammy®-nominated virtuoso bassist, composer, and producer whose genre-defying career spans over four decades, pushing the boundaries of what the bass can do in jazz, fusion, funk, and beyond. From touring with Stan Getz at age 19 to releasing more than 20 acclaimed albums, Bromberg’s discography includes tributes to legends like Jaco Pastorius, Scott LaFaro, Jimi Hendrix, and Jobim, as well as original works that top jazz charts worldwide. His pioneering use of piccolo bass and genre-blending arrangements have earned him widespread acclaim, chart-topping success, and collaborations with hundreds of music icons. Whether producing intricate acoustic jazz trios or high-energy smooth jazz recordings, Bromberg continues to innovate, inspire, and elevate the art of bass playing.

Interested in reprinting this article? Please review the reprint guidelines.

The National Association for Music Education (NAfME) provides a number of forums for the sharing of information and opinion, including blogs and postings on our website, articles and columns in our magazines and journals, and postings to our Amplify member portal. Unless specifically noted, the views expressed in these media do not necessarily represent the policy or views of the Association, its officers, or its employees.

Published Date

May 1, 2025

Category

- Innovation

Copyright

May 1, 2025. © National Association for Music Education (NAfME.org)