/ News Posts / Children’s Books: A Great Partner in the Music Classroom

Children’s Books

A Great Partner in the Music Classroom

By NAfME Member Suzanne Hall

This article first appeared in the March 2023 issue of Music Educators Journal.

Do you indulge in reading literature for personal enjoyment? Perhaps you are a collector of children’s books because of the diversity of topics or the colorful illustrations that capture your eye as you saunter through a bookstore. Alternatively, maybe you are captivated by the story told by the pages lying between the front and back covers.

I challenge you to consider that this love for literature can accompany music teachers in the classroom. Language arts teachers are not the only educators who can use stories and text as a vehicle for learning. Children’s literature in the elementary music classroom promotes imaginative play and contributes to exposure and dramatic arts involvement. Children love stories and enjoy being read to, and adding music to stories elevates them to another realm where the adventures come alive.

Why Children’s Books for Music Learning?

Children’s literature, including picture books, can be appropriate for any age level and can help students understand complex concepts, such as music. It can also engage students in music learning. Students garner a deeper comprehension of both the text and music when bringing children’s literature to life, and reading aloud enhances students’ enjoyment of the arts. Language arts acquisition and music acquisition share many commonalities, including sound discrimination, fluency, and comprehension, but the list of commonalities increases when discussing children’s books. Here are examples.

Children’s books provide opportunities for melodic and rhythmic reinforcement. The Froggy series by Johnathon London includes songs in the text, making it evident that Froggy, the main character, loves to sing. Music teachers can add a simple melody to the text or have students create their own melodies for the text.

Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See? by Bill Martin, Jr., can be a simple call-and-response song that allows students to reinforce the sol–la–mi pattern:

Children’s books also offer opportunities to develop music analysis, a challenging skill for some students. Students can use story elements to understand and describe music, making the musical concepts easier to grasp.

Let us consider the elements of a story. It begins with an author who contemplates an idea. This idea may expand to include a setting, plot, characters, conflict, and resolution. These elements are woven together to bring the idea (story) to life. The same concepts can be applied to assist students in analyzing music. For example, “Spring” from the Four Seasons by Antonio Vivaldi is a program piece that tells the story of two birds on a spring day. Using a story analysis chart, students can describe how the music reflects elements of a story. Students can discuss characters (bird—violin solos) and a change in setting (thunder and lightning represented by the brief shift to the minor key). This analysis can offer support for understanding abstract terms (e.g., dissonant [conflict] vs. consonant [resolution]). As a bonus, students can discuss how music and poetry can work hand in hand by reading the sonnets from which the piece is composed. Four sonnets were published with the original publication of the Four Seasons in 1725.[1] It is believed that Vivaldi wrote the sonnets that inspired the orchestral work. A sonnet accompanies each movement to tell the story of the seasons both musically and through the written word.

The following activities provide a snapshot of how music and children’s literature can create an in-depth musical experience.

Five Green and Speckled Frogs (K–1)

Retold and illustrated by Priscilla Burris

Music objective: (1) The learner will demonstrate tempo changes through movement. (2) The learner will dramatize the CD version (which reinforces expression) and compare and contrast it with a book version.

- Introduce the song Five Green and Speckled Frogs (from the Kimbo Educational CD). Have students make predictions about the story by looking at the illustrations on the front cover. (Anticipated responses include frogs, swimming, etc.)

- Select five students to be frogs and ten to be the pond (the rest can sing and pat the steady beat).

- Pass out masks and/or frog hats to the frog students and long strips of blue cloth to the ten students who will be the pond’s waves.

- Play Five Green and Speckled Frogs track (from the Kimbo Educational CD) and have the students dramatize the song. As the music plays, encourage the students to move the strips of cloth as waves to reflect the music’s tempo. When “One jumped into the pool” is heard, have a student “frog” jump in the water. The student can move or make swimming motions to music. By the end of the piece, five students should be moving among the waves.

- After the dramatization, ask the following: What happened to the music as it played? (It got faster.)

- Listen to the song again and have students demonstrate the change in tempo by patting the steady beat on their knees.

- Listen to the song one more time and have students follow along with the book.

- Compare and contrasts the lyrics and the text (Then vs. Now, “Yum” changes to “Crunch, Munch,” etc.).

- Extend the learning by comparing and contrasting different melodies with their book counterparts. Consider using a Venn diagram to help students visually see the comparisons. Examples include the following:

- Eensy Weensy Spider (Mary Ann Hoberman)

- I Know an Old Lady Who Swallowed a Pie (Allison Jackson)

- Five Little Monkeys (Kimbo Educational; Track 13)

The Little Old Lady Who Wasn’t Afraid of Anything (Grades 2–3)

By Linda Williams; illustrated by Megan Lloyd

Adding sound effects to any children’s book makes the abstract details of a story manageable to grasp. In the story The Little Old Lady Who Wasn’t Afraid of Anything, the little old lady walks through a scary forest. On the surface, students can grasp this narrative through the illustrations and text. However, hearing a scary forest and the creepy sounds the different clothing pieces make helps students understand the little old lady’s fear and why she begins to walk faster and faster.

Music Objective: (1) The learner will perform sound effects to a story. (2) The learner will perform rhythms that include quarter notes, eighth notes, and quarter rest.

- Discuss the role of sound effects in cinema, television, and radio.

- Tell students that they will be adding sound effects to the story.

- Assign students to play the rhythms of the following terms on instruments. Read the story and add the sound effects each time the words appear in the text. (For added effect, play Martha Stewart Living; Spooky Scary Sounds for Halloween as a background accompaniment to the reading; 2000, Rhino ASIN: B00004WJ6F.)

-

- Clomp, clomp (two shoes)—Hand drum

- Wiggle, wiggle (pants)—Guiro

- Shake, shake (shirt)—Maracas

- Clap, clap (gloves)—Castanets

- Nod, nod (hat)—Triangle

- Boo, boo (head)—Thunder sheet

- After reading, have students pair the terms with the rhythmic notation.

The Spider and the Fly (Grades 4–5)

By Tony DiTerlizzi

The Spider and the Fly is the perfect story to introduce the function of harmony, specifically how consonant and dissonant sounds can create a setting or mood. In this activity, the accompaniment creates the ominous feeling of the sly spider attempting to lure the innocent fly deeper into her lair in hopes of having the fly for her next meal.

Music Objective: Students will perform a simple accompaniment to a story.

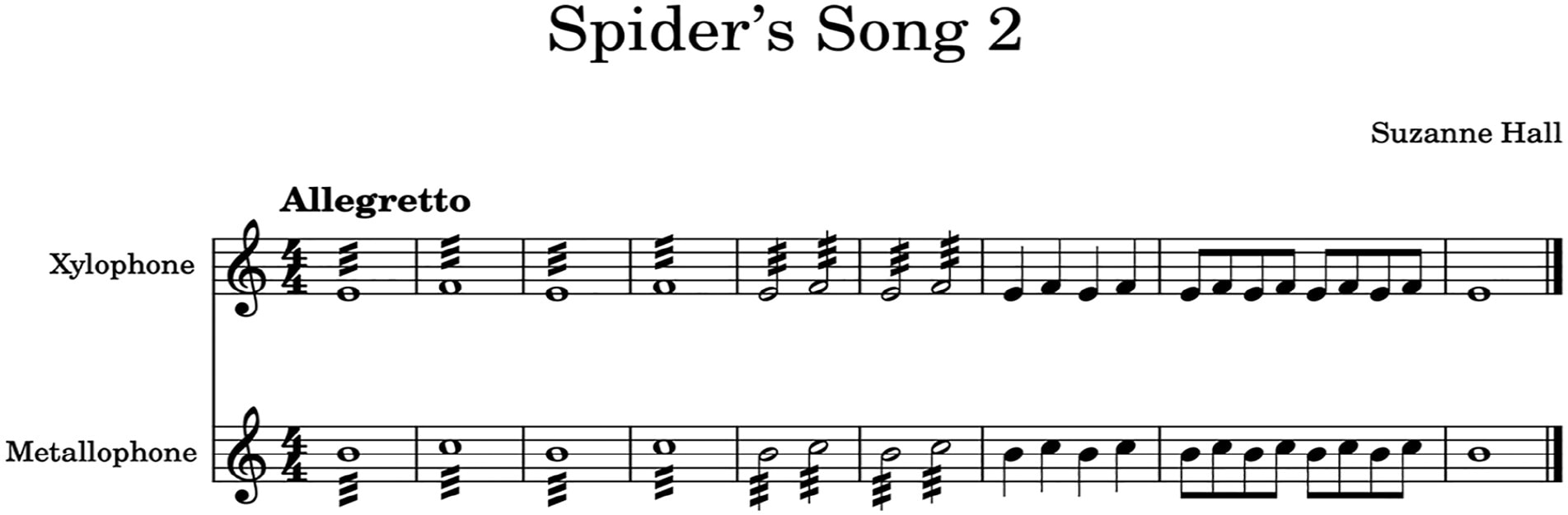

- Introduce Spider’s Song to students:

- Discuss the ascending pattern on the words “way up my winding stairs.”

- On pitched instruments, have some students play the ascending pattern to accompany the song. (Add a stroke on the triangle to represent the fly.)

- After singing the song, add the following sequence as the extension of the Spider’ song:

- Read the story and have students perform the musical accompaniment after the spider speaks on each page. For the last time, exclude the sound of the fly to represent the absence of the fly.

- Discuss how the musical sequence adds a sense of tension and anxiety that supports the eeriness of the text. Using the xylophone, demonstrate the sound tension by playing dissonant pitches together (e.g., B/C, E/F). Demonstrate consonant harmony as a resolution (e.g., B/C → C/G, E/F → E/C).

The illustrations in The Spider and the Fly provide significant insight into the story (the hallmark of an effective picture book), so much so that the text does not explicitly say the fly meets her demise. Instead, the reader can infer this occurred by the picture of the fly as a ghost. This concept parallels how music also supports visual stories, such as with movies in which the music prepares you for a scary moment or enhances an exhilarating car chase.

Music activities that involve children’s books can be fun and engaging and offer a new level of exposure to what music-making is. The breadth of experience can be vast, from seeing how harmony can reflect the setting or mood to how a simple melody can launch a storyline of an entire composition. Such experiences can be used to help review music elements and also reveal how elements can function in different ways. The activities in this article are a few ways you can use books in the music classroom and a fantastic way to merge your own love for literature with your love for music.

About the author:

NAfME member Suzanne Hall is an associate professor of music education in the Center for the Performing and Cinematic Arts, Boyer College of Music and Dance, Temple University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She can be contacted at suzanne.hall@temple.edu.

NAfME member Suzanne Hall is an associate professor of music education in the Center for the Performing and Cinematic Arts, Boyer College of Music and Dance, Temple University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She can be contacted at suzanne.hall@temple.edu.

Interested in reprinting this article? Please review the reprint guidelines.

The National Association for Music Education (NAfME) provides a number of forums for the sharing of information and opinion, including blogs and postings on our website, articles and columns in our magazines and journals, and postings to our Amplify member portal. Unless specifically noted, the views expressed in these media do not necessarily represent the policy or views of the Association, its officers, or its employees.

April 14, 2023. © National Association for Music Education (NAfME.org)

[1] Nicholas Lockey, “Antonio Vivaldi and the Sublime Seasons: Sonority and Texture as Expressive Devices in Early Eighteenth-Century Italian Music,” Eighteenth Century Music 14, no. 2 (2017): 265–83.

Published Date

April 14, 2023

Category

- Repertoire

- Standards

Copyright

April 14, 2023. © National Association for Music Education (NAfME.org)