/ News Posts / Curtains Up! Pathways to Theater and the Fine Arts during COVID-19

Curtains Up!

Pathways to Theater and the Fine Arts during COVID-19

By NAfME Member Brian Cyr

An abbreviated version of this article first appeared in the Connecticut Association of Boards of Education Journal.

The Backdrop

It was Thursday, March 12, 2020. After nine weeks of production and six months of planning, this was opening night of the Broadway musical Mamma Mia! at Maloney High School. With an amazing cast, beautiful sets, and hundreds of tickets sold, this was set to be the school’s biggest theatrical event in years. The cast was in make-up, the pit was warming up, and the doors were opening in an hour when the call came in. The superintendent began a conference call with our directional team, where we quickly learned that our school system would close effective the next morning, we would begin something called remote learning, and most impactful at the moment: opening night was now closing night of the show. The somber announcement to the cast unleashed a wave of tears and emotion, and it became clear that we were in uncharted waters, with so many questions and no answers. The tears subsided as the cell phones came out, texts sent, and calls frantically made so that family and friends could attend the one and only show on that Thursday night. For the next three hours, life went back to normal. The cast and crew performed the most incredible and emotional opening and closing night of Mamma Mia!

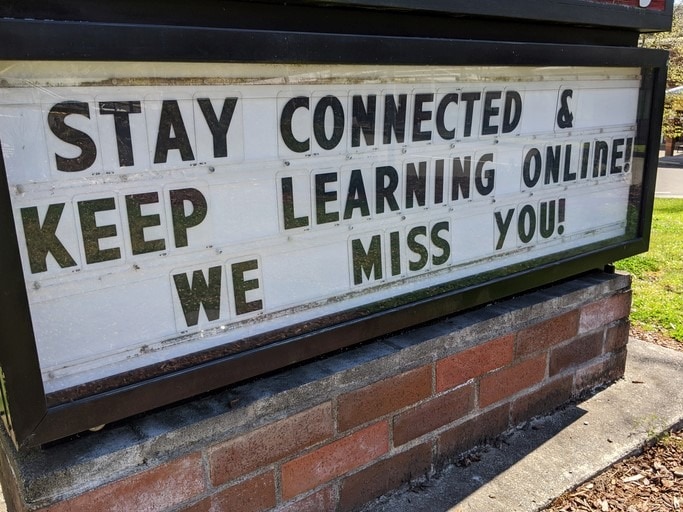

The days, weeks, and months ahead brought a global pandemic into focus and the fact that in-person learning and the arts as we knew it were not coming back anytime soon. As an administrative team, we quickly transitioned to at-home learning and The Meriden Public Schools were one of the first districts in the State of Connecticut to implement a distance-learning model. As we developed our strategies, guidelines, and processes for teaching and learning, maintaining active arts programs was a priority for all stakeholders. Cutting programs was not an option. We all agreed that all arts programs were to continue; we just needed a safe course of action.

The New Reality

For the remainder of the 2019–20 school year, K–12 classes immediately shifted to lessons assigned through Google Classroom and video sessions on Google Meet. Arts curricula was modified to take into account instruments left at school, art students without necessary supplies, and ensembles that were no longer together. A focus on found art and projects with household items took over the virtual art classrooms. Digital photography focused on what that iPhone camera can really do, and projects were photographed and submitted online. As projects came in, we redesigned our meridenarts.com website into a Distance Learning Visual Art Gallery and featured artwork created at home during the pandemic. In the music classrooms, groups transitioned to a focus on music theory, history, and pedagogy. Literature for performing ensembles was assigned through SmartMusic software, and other software titles like Soundtrap, Noteflight, and Musiquest were quickly introduced as supplemental tools in the music classroom. Video submissions of individual performances were submitted via Google Drive and Flipgrid, and the occasional Zoom performance was attempted. And while all of this was keeping the arts alive, our theater programs were in suspended animation. Back in March, we talked of the pandemic in weeks, not months or years. The spring shows in our secondary schools were pushed from April to May to June and then to the summer. Even Mamma Mia! closed with plans to perform the show again. After three new performance dates were scheduled and canceled, we finally struck the sets and cleared the stage of the show in August of 2020, and all secondary shows were closed.

“Cutting programs was not an option. We all agreed that all arts programs were to continue; we just needed a safe course of action.”

Our theater programs across the district had remained active all spring and summer, meeting over Zoom, rehearsing remotely, teaching stagecraft and in some cases performing over Zoom. But there was still no clear avenue to allow for active theater performances. Broadway was closed, local venues and amateur theaters were shuttered, and most theater events were canceled for the year.

The Arts Are Alive

As the fall school year started, our arts programs built on the successes of the spring remote session. We returned to in-person learning (with an option for distance learning) and a whole new set of norms. Active arts programs remained a priority, but the new realities presented a wealth of challenges. Marching Band began with field shows written for social distancing, all wind instruments were fitted with MERV-13 bell covers, indoor band rehearsals took place in auditorium seating areas or in small groups to allow for distancing, and performances were livestreamed to audiences. Orchestral and choral groups rehearsed in the same format, always in masks and often in small groups. Classroom music resumed with scheduling changes to allow for cohorting, and most teachers began to travel to classrooms to teach music and art in order to eliminate transitions and prevent mixing of cohorts.

While plans were in place for most of our K–12 arts programs, theater still presented us with the greatest challenge: how to safely sing, act, and dance together on a stage for an audience. As we progressed into mid-September, we met with local health officials and central office administration. The State of Connecticut also published two phases of clear guidelines for K–12 reopening specific to the safe operation of arts programs. After these meetings and reviews of state guidance, a normal theatrical show was simply not an option. District leadership was supportive of theatrical programs continuing, and all parties agreed to support productions if a safe process could be devised.

Within days, email communication from Music Theater International provided new options for streaming and on-demand performances. What was once forbidden was now possible—full-length Broadway shows could be now streamed to audiences. This started a whole new conversation. We were seeing theater activity performed on Zoom, with roles played from home. But with daily Google Meet classes a part of our student’s everyday life, announcing a production on a streaming platform was not likely to be met with much excitement. As we debated in production meetings, it became clear that we were looking at this challenge from the perspective of what the audience will see rather than what the students will experience. While a show on Zoom or Meet could work, it would take away many of the critical teaching aspects of the show such as blocking, personal interaction, and ensemble work and would eliminate many aspects of stagecraft that create the magic of the theater: lights, costuming, sets, effects, and more.

We felt some sort of in-person show was a must. The correspondence from MTI provided a listing of shows that could be licensed for streaming or on-demand viewing. Streaming would allow someone to tune in for a live video feed of the show, while on-demand would provide an opportunity to record a performance and then make it available to audiences. The discussion turned to on-demand and how that would work. As the discussions continued, the narrative began to sound as though we were making a movie more than a show. That was the moment we realized how to create a show safely and provide an incredible learning experience to our cast, crew, and orchestra performers: We needed to create a movie. We decided on the Broadway musical Little Women.

The Health Guidance

Our local health department gave us the green light to produce the show provided singers in masks remained at a six-foot distance. If the masks came off at any point, the distancing was twelve feet apart and for very short periods of time. No audiences were permitted, and all aspects of the show needed to be strictly monitored. The show needed to be designed in a manner that prevented any spread of COVID-19, and any positive cases in households or classes would result in quarantine of cast/crew members.

With an audience out of the question and an on-demand video looking like our sole end product, we reached out to a local videographer. We explained the situation and developed a plan to create a recording of Little Women. We explained that we wanted the show filmed, but not in the normal process of running the show from beginning to end. Because there was to be no audience, there was no need for a continuous recording. We felt that the show would be difficult to produce safely if we filmed the production from beginning to end. From quick set changes, to backstage costume changes, this is where we saw an increased risk of transmission—many people in close quarters moving quickly to keep with the timing of the scenes. To provide our students with a unique learning experience, we made plans to create a cinematic experience by recording scenes, some with multiple takes, with multiple camera angles and time in between to clear stage, ventilate the room, and choreograph the backstage work so minimal personnel were needed at any given time.

The design of show was developed based on health and safety guidance. Blocking was done with six- to twelve-foot spacing at all times, and masks were used in all rehearsals by all cast and crew members. Blocking with distance created challenges when the scene was intimate or very emotional, or when group dancing would normally take place. The role of Laurie would normally kiss Jo in Little Women. In our production, he leans in for the kiss, but he’s still six feet away. This was initially our biggest challenge. We were worried that we simply could not tell the story without the close proximities. As production developed, we learned how to maintain distances while still connecting characters, and we worked to create camera angles that gave the appearance of cast members being closer than they actually are.

Singing always created the most questions. We reviewed the latest aerosol studies, reviewed state guidance and worked with local health officials and all agreed that singing was safest at twelve-foot intervals and for shorter periods of time. All rehearsals were done in masks and scenes with singing were blocked with greater scrutiny and greater distancing. All rehearsals were done using lavalier microphones, which picked up the voices very well. While you do get a somewhat muffled tone when a singer is in a mask, it is certainly workable.

We used a live orchestra. All players (some students and some hired professionals) were seated a minimum of 12 feet apart in the pit area. In-ear monitors were used to connect all players and vocalists together, and the pit conductor was on a microphone through the monitor system. All pit musicians used MERV-13 bell covers and masks when they were not playing. Non-wind players and the conductor were always wearing masks. Discharge buckets were used by all brass players, and the flute player used a custom mask while playing. A house speaker system was not needed because there was no audience, so all audio work was focused on the in-ear monitoring and the development of a studio-quality recording of the show.

Set construction took place on a closed set with four to twelve workers per night in a socially-distant setting. Costuming, set dressing, and technical work all followed the same process: small groups in the space at separate times, always distanced and in masks, and always with attendance logs in case of contact tracing needs.

The Results

No transmission of COVID-19 occurred during any aspect of this production, but we did have positive cases in the cast/crew because of transmission within households. The mitigation strategies we put in place prevented transmission of the virus during rehearsals. We also dealt with students needing to quarantine due to close contact with positive cases. Throughout the eight weeks of production three pit musicians and eight cast members including two of the leads needed to quarantine due to possible exposure. We were able to work with a local recording studio to acquire audio software that could be used to connect with our musicians at home with minimal delay in order to allow real-time rehearsals with our cast members. We joined together on a Google Meet to see one another and then used audio-only software to connect and sing together.

The final taping was done over the course of two nights. Face masks on lead roles were removed for the final filming with proper distancing and permission from health officials. No live audience was present for any rehearsals or filming.

Five cameras with three operators were used to create the final product. In most cases camera operators were set up thirty feet from the performers in the open seating of the theater. We then worked with the studio to edit and produce the film in Adobe Premier.

After several days of editing the many video angles and different takes, Maloney’s production of Little Women went live for on-demand viewing at showtix4u.com on December 21, 2020. While an audience never saw the live show, cast and crew members were invited to the movie premiere—a private, black-tie affair, in the school theater where they were able to see their work on screen for the first time in a socially-distant setting.

At the conclusion of the premiere event, cast and crew members gathered in prom dresses (many from canceled proms the spring prior) and masks, and laughed and cried as they would at a cast party. As we witnessed their interaction, it became clear that we succeeded in giving our students an authentic, gratifying, and unique theatrical experience. While the audience was absent, the cinematic experience provided a safe, alternate means of learning and enjoyment that clearly impacted our students.

In Closing

While COVID-19 has changed so many aspects of our lives, the arts can safely remain active within our schools as long as we are willing to transform norms and find new avenues to create valuable learning experiences and provide our students with unique opportunities. The Meriden Public Schools has always been committed to maintaining K–12 arts programming throughout the pandemic, and this commitment has not only allowed us to keep the arts alive, but discover new opportunities for student growth. From digital galleries to cinematic theater to socially-distant marching bands, these new pathways to creation, performance, and presentation are driving our student successes during this most challenging time.

About the author:

NAfME member Brian Cyr has taught music for nineteen years and is currently the Fine Arts Coordinator for the Meriden Public Schools and the Director of Bands at Francis T. Maloney High School. Brian has taught at the middle and high school levels and currently teaches Concert Band, Competitive Marching Band, Jazz Ensemble, Music Technology, and Music Theory courses. Brian is a member of the Connecticut Music Educators Association and has held several positions in the organization, including Region Festival Director and Region Adjudication Chair, and has also conducted festival ensembles. Brian is also a proud member of CAAA (The Connecticut Arts Administrators Association) and ASBDA (The American School Band Directors Association). Recently, Brian has worked with the CAAA and a team with the Connecticut State Department of Education to create re-opening guidelines for K–12 arts programming during COVID-19 and remains active in promoting safe, active arts programs during the pandemic.

NAfME member Brian Cyr has taught music for nineteen years and is currently the Fine Arts Coordinator for the Meriden Public Schools and the Director of Bands at Francis T. Maloney High School. Brian has taught at the middle and high school levels and currently teaches Concert Band, Competitive Marching Band, Jazz Ensemble, Music Technology, and Music Theory courses. Brian is a member of the Connecticut Music Educators Association and has held several positions in the organization, including Region Festival Director and Region Adjudication Chair, and has also conducted festival ensembles. Brian is also a proud member of CAAA (The Connecticut Arts Administrators Association) and ASBDA (The American School Band Directors Association). Recently, Brian has worked with the CAAA and a team with the Connecticut State Department of Education to create re-opening guidelines for K–12 arts programming during COVID-19 and remains active in promoting safe, active arts programs during the pandemic.

Did this blog spur new ideas for your music program? Share them on Amplify! Interested in reprinting this article? Please review the reprint guidelines.

The National Association for Music Education (NAfME) provides a number of forums for the sharing of information and opinion, including blogs and postings on our website, articles and columns in our magazines and journals, and postings to our Amplify member portal. Unless specifically noted, the views expressed in these media do not necessarily represent the policy or views of the Association, its officers, or its employees.

March 17, 2021. © National Association for Music Education (NAfME.org)

Published Date

March 17, 2021

Category

- Ensembles

- Technology

Copyright

March 17, 2021. © National Association for Music Education (NAfME.org)