/ News Posts / No Time for Questions! Or Is There?

No Time for Questions! Or Is There?

Creating a Higher Level of Student Engagement

By Jenny L. Neff, Ed.D., Eastern Division Representative for the NAfME Council for Band Education

We hear a lot about teacher evaluation these days as a result of many education policy changes. Administrators continue to use various frameworks and rubrics to gather evidence for teacher ratings. These rubrics include planning and preparation, classroom environment, instruction, professional responsibilities, reflecting on teaching, and classroom strategies and behaviors (Danielson, 2007; Marzano, 2011). These areas are further subdivided into components that can be observed both in and outside the classroom. For example, Danielson’s Framework for Teaching divides instructional practices into high-quality questions, engaging discussion techniques, high levels of student participation, engaging activities and assignments, productive and appropriate grouping of students, suitable and engaging instructional materials and resources, and coherent lesson structure and appropriate pacing. My recent research in teacher evaluation revealed that the use of high quality-questions is one of the weakest areas of instructional practice in the classroom (Sartain, Stoelinga, &Brown, 2012).

This finding highlighted a new focus area for me—to assess the use of questions in rehearsals and classes. While I knew I asked and invited questions during rehearsal, reflecting on this piece of research allowed me to think about it from a new perspective. Did I ask high-quality questions that created a higher level of student engagement? Did my questions lead students to deeper thinking and content connections? Did the questions make rehearsal more meaningful and purposeful for everyone? Did the students, in turn, ask high-quality questions?

In music, sometimes the role of director can easily become that of direc-tator. Rehearsal time is limited and at times even rushed. It can be difficult, if not impossible, to stop rehearsal to ask questions. However, through questions students become more immersed in musical knowledge, skills, decision-making, and reflective thinking. And they may even ask high-level questions themselves.

Asking students the right kinds of questions can engage them as learners and musicians who develop a deeper understanding of their craft. The following examples provide ways to include purposeful, high-quality questions during instrumental classes or rehearsals.

Example 1: Questions in the Form of Exit Tickets

An exit ticket is an assessment tool that provides feedback to the teacher and is used at the end of class. When used in the right way, it can also connect meaning to what we do in the classroom by including purposeful questions.

As ensemble directors we frequently refer to levels of listening. For example, an ensemble may describe these as: “level 1”—students listening to themselves; “level 2”—students listening to their section or others near their section; and “level 3”—students expanding to include listening to the full ensemble. These levels are frequently outlined as steps to achieve balance, blend, and intonation within the ensemble (Lisk, 1991). In order to connect exit tickets to these classroom concepts purposefully, band members respond to questions that directly reflect on listening levels. The feedback from students on the exit tickets can identify what they are or are not hearing as well as trouble spots they may identify in their music. See Figure 1.1.

Exit tickets can also be reviewed for future planning. Common themes can alert the director to focus on uncertain areas. For example, a percussionist who sites a 9-stroke roll as an area for improvement might communicate the need to practice this skill during a lesson or sectional. Similarly, students who identify a concept such as syncopation or cut time identify a gap in knowledge that may need to be re-taught or reviewed. The director might also determine focus areas for the next rehearsal that affect the group as a whole (e.g., blend and balance; showing similarities and differences among parts; tempo changes, etc.). And student comments can even reveal behavior problems within the ensemble (e.g., excessive talking, conflict within a section, etc.). Using student feedback from the exit tickets for future planning can help improve the ensemble on all levels—individual, section, and full ensemble.

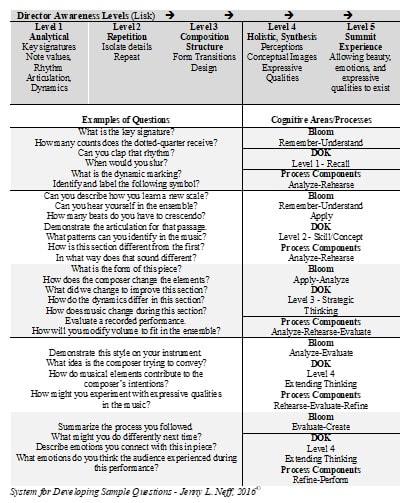

Example 2: Questions During Stages of Rehearsal

While making music at higher aesthetic levels is not achieved by simply completing a series of charts and checklists, sometimes a systematic approach to delivering instruction can help us prepare lessons that lead our students to reach higher aesthetic goals. Figure 1.2 is a systematic chart I created to include higher-level questioning during rehearsals. It includes musical practices used at various stages of rehearsal (Lisk’s Director Awareness Levels) as the overarching process, and then outlines a district-specific goal (Webb’s Depth of Knowledge) with a time-tested educational hierarchy (Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy). When combined with the process components from NAfME’s 2014 Music Standards, this provides a basic framework for formulating and scaffolding questions for instruction. Lisk’s Director Awareness Levels follow a continuum of analytical, repetition, composition structure, holistic/synthesis, and summit experiences. While higher-level questions from Bloom’s Taxonomy can be formulated and asked at any of the Director Awareness Levels, a starting point for including more questions might be to align the awareness levels with the specific levels of Bloom. The goal is to ask higher-level questions of our students at every stage. While many bands can get stuck in the beginning stages of the rehearsal continuum (i.e., analytical, repetition, and composition structure), thoughtful questions can help move the ensemble onto higher aesthetic levels, leading to a better performance.

Any of these elements could be customized to meet one’s musical practices, district requirements, and teaching style. Similarly, applying this process to a specific piece of music could allow one to cover many facets of the piece from background, musical knowledge, and vocabulary to creating deeper musical meaning. For me, trying to include a certain number of high-quality questions in each class/rehearsal was a good starting point. I often wrote specific questions in my rehearsal plans for later reflection. This allowed me to identify which levels had been included, overused, or missed.

Example 3: Bringing the P.I.E.

One of the phrases I use almost daily in my own teaching and with new teachers is, “Where is the P.I.E.?” It stands for purposeful, intentional, and explicit. When going through professional development on using critical and creative thinking skills in a former district, I found this question made a huge difference in the classroom. When planning for instruction and teaching students, it is important to make sure you bring the P.I.E. to each lesson and rehearsal. Being purposeful, intentional, and explicit about what we do in the classroom is common in all content areas. Thus, it can be part of a larger conversation we have with colleagues inside and outside of music.

Some teachers worry about including a district-mandated goal into their lessons for fear of taking way from rehearsal time or music activities. Perhaps the method by which that goal is included in a lesson or rehearsal can define the level of musical engagement. For example, if the district has required a literacy or writing goal, the framework (Figure 1.2) can help maintain a purposeful musical path. Lisk’s Director Awareness Levels can still guide the rehearsal.

Bloom’s taxonomy can still ensure that various levels of questions and learning take place. But, being purposeful about how the literacy-related activity is included can be crucial in whether or not students stay the musical course.

Figure 1.2 Sample Questions

Think of something that intentionally provides deeper music connections. For example, you may have students read background information on the musical time period or composer you are studying. They could easily code the text (e.g., place a star next to something they feel is important, place a question mark next to something they don’t understand, etc.). This sort of activity does not take away from the musical part of the lesson but rather adds to students’ background knowledge in the content area. Similarly, they could learn about the piece of music and then write their own program notes or concert review. Any of these basic examples can add to deeper content connections if implemented in a purposeful, intentional, and explicit manner.

Another way to bring the P.I.E. to asking questions in your teaching is to re-evaluate something you already do and upgrade the lesson to reach a new depth of the music-making. For example, many directors ask kids to change their seats in the ensemble as a fun sort of break from the rehearsal norm. However, asking questions that lead students to understand the purpose and intention behind the activity in an explicit way can develop a new perspective. This past summer while conducting at a music camp, we did the “band scramble” (changed their seats). The tubas immediately moved to the front row exclaiming, “This is our dream!” The questions I asked the band afterward led to the purpose of why I did the activity in the first place. Before we played, I asked, “Why would I have you change seats?” Their responses included statements along the lines of “to hear things differently.” After we played a march, I asked, “What did you notice while sitting in your new seat in the ensemble? What did you hear?” The student responses explained to the group exactly why I had done the activity, and included statements like “I felt more independent”; “I had to rely on myself instead of my section”; “I had to focus more”; “I heard a countermelody in the clarinets I had not heard before”; “I could hear different sections more easily”; “I heard different people who played the same part as me.”

Expanding the content of rehearsal questions away from simply regurgitating memorized facts and fingerings toward developing a deeper understanding of musical meaning helps promote student engagement at all stages. By purposefully, intentionally, and explicitly asking high-quality questions during rehearsal, students will think more deeply about what they do and how they think and process ideas as growing musicians. While it may take more time in the beginning, it may save time in the end and help students better understand how to reach new aesthetic levels.

About the author:

Photo credit: Sherri Ciancutti Sabatino

NAfME member Jenny L. Neff, Ed.D., teaches Instrumental Music at Bala Cynwyd Middle School in Lower Merion School District. She is also the Director of the M.M. and Summer Music Studies at University of the Arts in Philadelphia. She currently serves as the Eastern Division Representative for NAfME’s Council for Band.

Did this blog spur new ideas for your music program? Share them on Amplify! Interested in reprinting this article? Please review the reprint guidelines.

The National Association for Music Education (NAfME) provides a number of forums for the sharing of information and opinion, including blogs and postings on our website, articles and columns in our magazines and journals, and postings to our Amplify member portal. Unless specifically noted, the views expressed in these media do not necessarily represent the policy or views of the Association, its officers, or its employees.

November 30, 2017. © National Association for Music Education

Published Date

November 30, 2017

Category

- Classroom Management

- Ensembles

Copyright

November 30, 2017. © National Association for Music Education (NAfME.org)