/ News Posts / Tips on Student Teaching

Tips on Student Teaching

A Digest of Resources for Pre-Service Music Teachers

By NAfME Member Paul K. Fox

© 2019 Paul K. Fox

This article first appeared on Paul Fox’s blog here.

If you are not fortunate enough to own a copy of A Field Guide to Student Teaching in Music by Ann. C. Clements and Rita Klinger (which I heartily recommend you go out and buy, beg, borrow, or steal), this blog provides a practical overview of field experiences in music education, recommendations for the preparation of all music education majors, and a bibliographic summary of additional resources. Representing that most critical application of in-depth collegiate study of music education methods, conducting, score preparation, ear-training, and personal musicianship and  understanding of pedagogy on voice, piano, guitar, and band and string instruments, the student teaching experience provides the culminating everyday “nuts and bolts” of effective music education practice in PreK–12 classrooms.

understanding of pedagogy on voice, piano, guitar, and band and string instruments, the student teaching experience provides the culminating everyday “nuts and bolts” of effective music education practice in PreK–12 classrooms.

Possibly the best definition of “a master music teacher” and the process for “hands-on” field training comes from the Penn State University handbook, Partnership for Music Teacher Excellence: A Guide for Cooperating Teachers, Student Teachers, and University Supervisors.

“The goal of the Penn State Music Teacher Education Program is to prepare exemplary music teachers for K–12 music programs. Such individuals can provide outstanding personal and musical models for children and youth and have a firm foundation in pedagogy on which to build music teaching skills. Penn State B.M.E. graduates exhibit excellence in music teaching as defined below.”

“As PERSONAL MODELS for children and youth, music teachers are caring, sensitive individuals who are willing and able to empathize with widely diverse student populations. They exhibit a high sense of personal integrity and demonstrate a concern for improving the quality of life in their immediate as well as global environments. They establish and maintain positive relations with people both like and unlike themselves and demonstrate the ability to provide positive and constructive leadership. They are in good mental, physical, and social health. They demonstrate the ability to establish and achieve personal goals. They have a positive outlook on life.”

“As MUSICAL MODELS, they provide musical leadership in a manner that enables others to experience music from a wide variety of cultures and genres with ever-increasing depth and sensitivity. They demonstrate technical accuracy, fluency, and musical understanding in their roles as performers, conductors, composers, arrangers, improvisers, and analyzers of music.”

“As emerging PEDAGOGUES, they are aware of patterns of human development, especially those of children and youth, and are knowledgeable about basic principles of music learning and learning theory. They are able to develop music curricula, select appropriate repertoire, plan instruction, and assess music learning of students that fosters appropriate interaction between learners and music that results in efficient learning.” — Penn State University School of Music

Making a smooth transition from “music student” to “music teacher” requires a focus on four goals:

- Preparation to your placement in music education field assignments

- Understanding of the relationships between your cooperating teacher(s) and the university supervisor (and you!) and promotion of positive communications

- Adjusting to new environments

- Development of professional responsibilities

As mentioned before, details of these should be reviewed in a reading of the introduction to A Field Guide to Student Teaching in Music by Ann. C. Clements and Rita Klinger.

Not to “toot my own horn,” but you are invited to peruse my past blogs on this subject:

- Transitioning from Collegiate to Professional – Part I

- Transitioning from Collegiate to Professional – Part II

- Transitioning from Collegiate to Professional – Part III

Observations

“Take baby steps,” they say? Before your college music education professors release you to direct a middle school band, teach a general music class, or rehearse the high school choir, you will be asked to observe as many music programs as possible.

“Regardless of your formal assignments by your music education coordinator, try to find time to observe a multitude of different locations, levels, and socioeconomic examples of music classes.”

My advice to all pre-service teachers is, regardless of your formal assignments by your music education coordinator, try to find time to observe a multitude of different locations, levels, and socioeconomic examples of music classes. Do not limit yourself to those types of jobs you “think” you eventually will seek or be employed:

- Urban, rural, and suburb settings in poor, middle, and upper-middle socioeconomic areas

- Large and small school populations

- Both private and public school entities

- Elementary, middle, and high school grades

- General music, tech/keyboard, guitar, jazz, band, choral, and string classes

- Assignments as different from your own experiences in music-making

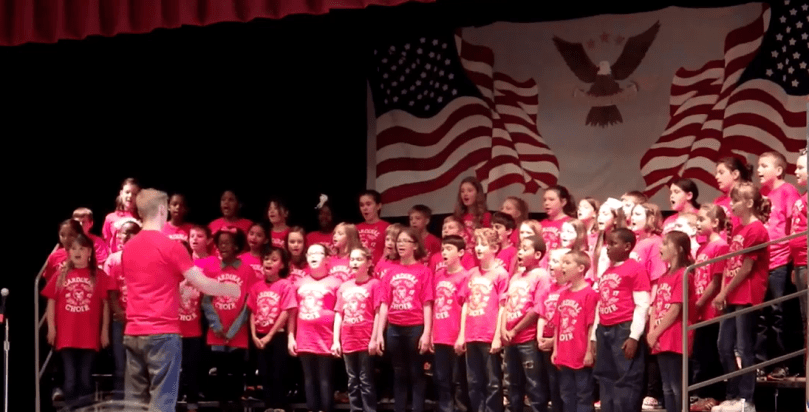

Photo courtesy of David Dockan, JEJ Moore Middle School, Prince George, VA

Ann Clement and Rita Klinger make the distinction between simply observing and analyzing what you see:

“Observation is a scientific term that means to be or become aware of a phenomenon through careful and directed attention. To observe is to watch attentively with specific goals in mind. Inference is the act of deriving logical conclusions from premises known or assumed to be true. Inference is the act of reason upon an observation. A good observation will begin with pure observation devoid of inference. After an observation of the phenomenon being studied has been completed, it is appropriate to infer meaning to what has been observed. Adding inference after an observation completes the observation cycle—making it a meaningful observation.” — A Field Guide to Student Teaching in Music

Some tips (from Student Teaching in Music: Tips for a Successful Experience by Blair Chadwick and Dr. Johnathan Vest):

- Have a specific goal for the observation in mind before you begin.

- Make copious notes, but don’t write down everything.

- Write down techniques, quotes, musical directions, or teacher behaviors that seem important.

- Don’t be overly critical of your master or cooperating teacher during the observation process. Remember, they are the expert, you are the novice. Your perspective changes when you are in front of the class.

- Hand-write your notes. An electronic device, although convenient, is louder and can be a distraction for the teacher and students, and you. Write neatly so you can transcribe the notes later.

- A small audio recorder can be very useful in case you want to go back and hear something again.

It is appropriate to mention something here about archiving your notes and professional contacts. It is essential that you organize and compile all the data as you go along . . . catalog the information in your “C” files (don’t just stuff papers in a drawer somewhere):

- Contacts (cooperating/master teachers and administrators’ phone/email addresses)

- Course work outlines and class observation journals

- Concerts (your own solo and ensemble literature and school repertoire)

- Conferences (session handouts, programs)

Why is this important? Don’t be surprised if/when you are asked to teach in a specialty or grade level outside your “major emphasis,” and you want to find that perfect teaching technique or musical selection previously observed that would be a help in your lesson.

Student Teaching

The success of the student teaching experience depends on all its parts working together. They include:

- The Student Teacher

- The Cooperating Teacher

- The University Supervisor

- The Students

- The Administration and other teachers and personnel in the building

Photo courtesy of David Dockan, JEJ Moore Middle School, Prince George, VA

First, check out your university’s guidelines (of course), but here are “The Basics.”

- Punctuality (Early = on time; On time = late; Late = FIRED)

- Dress and Appearance: Be comfortable yet professional. Be aware of a dress code if one exists, as well as restrictions on tattoos, piercings, and long hair length (gentlemen).

- Parking/Checking-In: Know this information BEFORE your first day.

- Materials and Paperwork: Contact your Cooperating Teacher BEFORE the first day. Know what you need and bring it with you on the first day.

Teacher Hub in “A Student Teaching Survival Guide” spelled out a few more recommendations:

- Dress for success (professionally)

- Always be prepared (checklists, planner, to-do’s)

- Be confident and have a positive attitude (if needed, “fake” self-confidence)

- Participate in all school activities (everything you can fit into your schedule: staff meetings, extra-curricular activities assigned to the cooperating teacher, and even chaperone duties for a school dance, etc.)

- Stay clear of drama (no gossip!)

- Don’t take it personally (embracing constructive feedback and criticism)

- Ask for help (that’s why you and mentor teachers are there)

- Edit your social media accounts (privacy settings and no school student contacts)

- Approach student teaching as a long interview (always, throughout the student teaching assignment: “best foot forward” and showcase of all of your qualities)

- Stay healthy (handling stress, good sleep, and other positive health habits)

Common questions that may be asked by the student teacher (Chadwick and Vest):

- Will my cooperating teacher (CT) and school be a good fit for me?

- Will I “crash and burn” my first time in front of the class?

- What if my CT won’t let me teach?

- What if my CT “throws me to the wolves” on the first day?

- Will the students respect me?

- How will I be graded?

- Will I pass the Praxis??

Planning

Chapter 2 “Curriculum and Lesson Planning” in A Field Guide to Student Teaching in Music provides twelve pages covering scenarios, discussions, and worksheets on all aspects of instructional planning, including the topics of philosophy of music teaching, teaching with and without a plan, long-term planning, and assessment and grading.

If you are unfamiliar with the terms “formative,” “summative,” “diagnostic,” and “authentic” assessment, or other educational jargon, or are not fully aware of your state’s arts and humanities standards and the National Core Arts Standards, don’t panic. (Many of us “veteran” music teachers were in the same boat at the beginning of student teaching, regardless of how much material was introduced in our education methods courses.) Do some “catch-up” by visiting the corresponding websites. For example, in Pennsylvania, you should be a member of PCMEA and take advantage of the research of the PMEA Interactive Model Curriculum Framework. Some educational “buzz words” and acronyms were explored in a previous blog here. It should be noted that, although you won’t be expected to know the full PreK–12 music curriculum while student teaching, when you are hired as “the music specialist,” you would likely be the professional who will be assigned to write and update that same curriculum . . . so get to know it ASAP. (On my second day in my first job, my JS/HS principal came to me and said a course of study for 8th grade music appreciation was due on his desk by the last week of the semester! No, like you, I was not trained in writing curriculum in college!)

Photo courtesy of David Dockan, JEJ Moore Middle School, Prince George, VA

From the Penn State University Partnership for Music Teacher Excellence: A Guide for Cooperating Teachers, Student Teachers, and University Supervisors, the following criteria are recommended to be used by the cooperating teacher and the student teacher to assess the effectiveness of a long-term course of study. (Sample plans are provided here.)

- Stated learning principles are related to specific learner or student teacher

activities. - The importance of the course of study is explained in terms learners would likely

accept and understand. - Each goal is supported by specific objectives.

- The sequence of the objectives is appropriate.

- The goals and objectives are realistic for this group of learners.

- The objectives consider individual differences among learners.

- The content presentation indicates complete and sequential conceptual

understanding. - The presentation is detailed enough that any teacher in the same field could

teach this unit. - The amount of content is appropriate for the length of time available.

- A variety of teaching strategies are included in the daily activities.

- The teaching strategies indicate awareness of individual differences.

- The daily plans include a variety of materials and resources.

- The objectives, teaching strategies, and evaluations are consistent.

- A variety of evaluative techniques is employed.

- Provisions are made for communicating evaluative criteria to learners.

- The materials are neatly presented.

It is important sit side-by-side with your cooperating teacher and discuss some of these “essential questions” of instructional planning and assessment of student teaching:

- What is the purpose of the learning situation?

- What provision have you made for individual differences in learner needs, interests, and abilities?

- Are your plans flexible and yet focused on the subject?

- Have you provided alternative plans in case your initial planning was not adequate for the period (e.g., too short, too long, too easy, too hard)?

- Can you maintain your poise and sense of direction even if your plans do not go as you anticipated?

- Can you determine where in your plans you have succeeded or failed?

- On the basis of yesterday’s experiences, what should be covered today?

- Have you provided for the introduction of new material and the review of old material?

- Have you provided for the development of musical understanding and attitude as well as performance skills?

Getting Your Feet Wet . . . Becoming an “Educator”

[Source: Chadwick and Vest]

Be attentive to the needs of the students and your cooperating teacher. If you see a need that arises that the CT cannot address, or is not addressing, then take action. Don’t always wait to be told what to do. These situations may include:

- Singing or playing with students who are struggling

- Work with a section or small group of students

- Helping a student with seat/written work

- Attending to a non-musical problem (such as student behavior)

Photo courtesy of David Dockan, JEJ Moore Middle School, Prince George, VA

Your supervising teacher or music education coordinator will probably instruct you on how much and when to teach, but each school and CT is different. In general, you should start teaching a class full-time by week three and have at least two weeks of full-load teaching per placement. (This is not always possible.)

Remember that any experience is good experience, so be grateful if you are asked to teach early-on in your experience.

What the supervising and/or cooperating teachers are looking for during an observation:

The Lesson Plan

- Lesson organization (components, logical flow, pacing, time efficiency)

- Required components included

- National and State Standards included—and these have changed/are changing!!

- Objectives stated in observable terms and tied directly to your assessment(s)

- What the US/CT is looking for during an observation

Teaching Methods

- Questioning techniques (stimulate thought, higher order, open-ended, wait time)

- Appropriate terminology use

- Student activities that are instructionally effective

- Teacher monitoring of student activities, assisting, giving feedback

- Opportunities for higher order thinking

- Teacher energy/enthusiasm

Classroom Management

- Media and materials are appropriate, interesting, organized, and related to the unit of study

- Teacher “with-it-ness”

- Student behavior management (consistency, classroom procedures in place, students understand expectations)

Student Involvement/Interest/Participation in the Lesson

- Student verbal participation

- Balance of teacher talk/student talk

- Lots of “musicing” (singing, playing, listening, moving)

- Student motivation

- Student understanding of what to do and how to do it

Classroom Atmosphere

- Positive, “can-do” atmosphere

- Student questions, teacher response

- Helpful feedback

- Verbal and non-verbal evidence that all students are accepted and feel that they belong

Student teaching is the opportunity of a lifetime. This is when you get to practice your pedagogical skills, make invaluable professional connections, and learn lifelong lessons. Sure, it will take a lot of hard work and dedication. As TeacherHub concluded, “Use this time to learn and grow and make a great impression. Stay positive and remember student teaching isn’t forever—if you play your cards right, you will have a classroom of your own very soon.”

Acknowledgments: Special thanks for the contributions of Blair Chadwick and Johnathan Vest, who gave me permission to share information verbatim from their PowerPoint presentation, and to John Seybert (formerly of Seton Hill University), Ann C. Clements, Robert Gardner, Steven Hankle, Darrin Thornton, Linda Thornton, and Sarah Watt (Penn State University), Dr. Rachel Whitcomb (Duquesne University), and Robert Dell (Carnegie-Mellon University).

Photo credits: David Dockan, my former student, graduate of West Virginia University, now Choir Director / Music Teacher at JEJ Moore Middle School in Prince George, VA.

Bibliography

A Field Guide to Student Teaching in Music, Ann C. Clements and Rita Klinger

A Guide to Student Teaching in Band, Dennis Fisher, Lissa Fleming May, and Erik Johnson, GIA 2019

Handbook for the Beginning Music Teacher, Colleen Conway and Tom Hodgman, 2006

Including Everyone: Creating Music Classrooms Where All Children Learn, Judith A. Jellison, 2015

Intelligent Music Teaching, Robert Duke

Music in Special Education, Mary S. Adamek and Alice Ann Darrow, 2010

Partnership for Music Teacher Excellence: A Guide for Cooperating Teachers,

Student Teachers, and University Supervisors, Penn State University Music Education Faculty Ann Clements, Robert Gardner, Steven Hankle, Darrin Thornton, Linda Thornton, Sarah Watts

Remixing the Classroom: Toward an Open Philosophy of Music Education, Randall Everett Allsup, 2016

A Student Teaching Survival Guide, Janelle Cox

Student Teaching in Music: Tips for a Successful Experience, Blair Chadwick and Dr. Johnathan Vest

Teaching Music in the Urban Classroom, Carol Frierson-Campbell, ed.

Teaching with Vitality: Pathways to Health and Wellness for Teachers and Schools, Peggy D. Bennett, 2017

About the author:

Paul K. Fox, a NAfME Retired Member, is Chair of the PMEA State Council for Teacher Training, Recruitment, and Retention. He invites you to peruse his “marketing professionalism” blog-series (in reverse chronological order) at his website.

Paul K. Fox, a NAfME Retired Member, is Chair of the PMEA State Council for Teacher Training, Recruitment, and Retention. He invites you to peruse his “marketing professionalism” blog-series (in reverse chronological order) at his website.

Did this blog spur new ideas for your music program? Share them on Amplify! Interested in reprinting this article? Please review the reprint guidelines.

The National Association for Music Education (NAfME) provides a number of forums for the sharing of information and opinion, including blogs and postings on our website, articles and columns in our magazines and journals, and postings to our Amplify member portal. Unless specifically noted, the views expressed in these media do not necessarily represent the policy or views of the Association, its officers, or its employees.

Catherina Hurlburt, Marketing Communications Manager. January 28, 2020. © National Association for Music Education (NAfME.org)

Published Date

January 28, 2020

Category

- Collegiate

- Music Educator Workforce

Copyright

January 28, 2020. © National Association for Music Education (NAfME.org)