/ News Posts / How ‘Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood’ Impacted Music Education

How Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood Impacted Music Education

By Mary Rogelstad

This article was originally posted on Cued In, the J. W. Pepper blog.

It’s said the first thing Fred Rogers did when he returned home from emergency surgery for stomach cancer was go straight to his piano. His wife Joanne has shared with friends how much her husband loved playing that piano. His grandmother bought the nine-foot Steinway concert grand for Fred when he was only a teenager. He used that piano for the rest of his life, including when he composed songs for Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood and when he played some of his favorite pieces, like Misty.

“Joanne has described standing in the next room until Fred finished when he was playing with such reverie,” Faulkner University professor Art Williams said.

Image courtesy of J. W. Pepper

Williams has extensively studied how Mister Rogers has affected music education. Like many others, Williams grew up watching the program. When Williams was in high school, he wrote letters to both Fred Rogers and the program’s jazz pianist, Johnny Costa. Both of them wrote him back with words of encouragement. Costa inspired Williams to study music education.

“Looking back, I realized to what extent the music on Mister Rogers influenced my love of jazz and my desire to study music,” Williams said.

That effect was so strong for Williams and many others because of the ways both music and child psychology concepts were treasured on the program.

The Musical Foundation of Mister Rogers

Much of the show’s philosophy stemmed from Rogers’ experiences with his grandfather, Fred Brooks McFeely. As the Los Angeles Times noted, Rogers told book writer Jeanne Marie Laskas that his grandfather once said to him, “You know, you made this day a really special day just by being yourself. There’s only one person in the world like you, and I happen to like you just the way you are.”

Johnny Costa wrote down simplified versions of his jazz arrangements before he passed away in 1996. His work inspired other artists like Paul Murtha to publish arrangements like this one for today’s students.

That idea stuck when Rogers later attended Rollins College to major in music composition. When Rogers began his television program, he worked hand in hand with renowned child psychologist Dr. Margaret McFarland to ensure he could create songs that would reach young viewers. Rogers wrote more than 200 songs for his TV neighborhood, concentrating primarily on the lyrics and the melody.

Costa and his jazz trio provided the flourish. Costa was a master pianist who was highly regarded for his ability to improvise. He altered his piano playing every time a song was played, including the opening and closing numbers. He also improvised when Rogers was talking, setting the stage for Rogers to powerfully convey his messages.

From the first sounds of the program to the last, Costa was determined not to dumb down any of the music. The opening piano notes in Won’t You Be My Neighbor that started each episode were inspired by the fourth movement of Beethoven’s Sonata in C Major, Opus 2, No. 3.

“Johnny was working on the Beethoven sonata and thought it would make a nice intro if he just put his thumb down while playing to create four-part harmony instead of three,” Williams said.

Rogers composed Won’t You Be My Neighbor in 1963 after the show began in Canada. It was kept when the program transferred to the United States. The original closing number for Mister Rogers though was a composition called Tomorrow (listen to it here on YouTube). Rogers wrote It’s Such a Good Feeling in 1969, which was later adopted as the traditional closing.

These pieces helped create the musical foundation of the show.

“Fred said music was the heartbeat of it all. The program has a musical grid. He even composed the script in sonata form,” Williams said.

He explains that the exposition of the “sonata” was when Rogers brought an object that would set forth the idea of the day. The development would include travels as the viewer saw how the idea unfolded. The recapitulation was when Rogers revisited and interpreted what had been done that day.

Underlying it all was the show’s patient pace. Composer Tom Trenney, who also credits Mister Rogers with inspiring his life’s work, says the program’s use of routine and reflective moments can be duplicated in the music classroom and beyond.

“We often do the same thing again and again to create some calm,” Trenney said. “There’s a joy in resting and gently creating quiet space. A moment of silence in choir rehearsal can make the music much more intentional.”

Ways the Show Influenced Music Education

Beyond the overall structure of the program, Mister Rogers had specific ways it promoted music education and child development. Williams defined six ways in his dissertation:

- Original Compositions– The songs on the program demonstrated how powerful it is to combine lyrics with melody in ways that help an audience address common aspects of life. For children, that included everything from welcoming a baby brother or sister to dealing with fears about going down the bathtub drain. The program also frequently discussed how to handle emotions.

- Music Underscore – Williams says that with the help of Costa, the music became “a character of its own.” The improvised jazz played throughout the program was unlike anything children would have heard on other shows at the time.

- Operas Composed – Thirteen children’s operas were produced for the show. Rogers’ former classmate John Reardon was an opera singer who performed in the works. The program showed the process of creating the opera throughout the week so children could see the collaboration involved in the production.

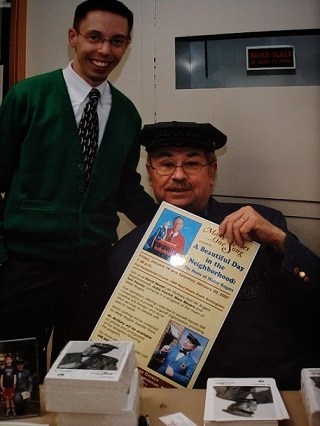

Fred Rogers and Art Williams on the set of “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” on April 10, 1997. Photo courtesy of Art Williams. All rights reserved.

- Musical Guests – The program frequently featured musicians, both professional and amateur. Guests were regularly asked if they enjoyed playing as a child and how they played if they had strong emotions, including sadness or anger. Famous guests included cellist Yo-Yo Ma, trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, singer Tony Bennett, violinist Hilary Hahn and pianist André Watts. Grammy award-winning artist Esperanza Spalding has said seeing Yo-Yo Ma on an episode inspired her to learn how to play the bass.

- Music Lessons – Rogers frequently had segments designed to teach children about music. He showed how instruments were made, shared a staff with notes, and went to the music shop on the set for lessons. Williams says Rogers followed the Quaker idea that “attitudes are caught, not taught.” With that mind, he enjoyed featuring professionals who not only loved what they did but also worked hard to achieve their goals.

- Musical Messages – Music was always presented in a positive light on the program. Rogers would ask the children if music made them feel like singing or dancing and what instruments they may like to play. The set also included posters on the walls and other visible things that encouraged music lessons and positive attitudes towards music. It was the best form of subliminal advertising.

The combined effect was that children continually were exposed to noteworthy details about music. As Williams said, “It was probably the largest music appreciation classroom there’s ever been.”

The Big Message for Educators

Trenney focused on these big-picture ideas during a presentation on Mister Rogers at the National Conference of the American Choral Directors Association. As a composer and conductor, Trenney has taken to heart Rogers’ practice of regularly sharing thoughts about how we should treat our neighbors with openness and inclusion. Trenney keeps that in mind when picking text for his compositions and repertoire for his choirs to sing.

Composer Tom Trenney has given multiple presentations about “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.” Here he poses with David Newell, who played Mr. McFeely, at a fundraiser for people with special needs. Photo courtesy of Tom Trenney

“We should use the holy ground of choir to sing about love, hope, light and faith. If we don’t do it in treasured times when we choose the words on people’s lips, who are we looking to do that?” Trenney said.

Trenney also appreciated Rogers’ gentle nature in a world and time when men were often expected to be tough. Trenney says it’s notable that Rogers always stayed true to who he was.

“Think about how much the world changed in the 30 years from 1968 until the early 2000s. And you know he had the same curtains and the same sweaters the whole time,” Trenney said. “It wasn’t about being novel and trendy. It was about having a message that said to somebody, ‘I love you just the way you are. There’s no one else like you. There never has been, and there never will be.’”

You can learn more about Fred Rogers at the Fred Rogers Center in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, and at Fred Rogers Productions.

View works by Fred Rogers here.

J.W. Pepper is a corporate member of the National Association for Music Education.

About the author:

Mary Rogelstad joined Pepper in 2018 as the company’s Marketing Content Coordinator. Previously she worked as a journalist in the international media and as a communications specialist at various nonprofits. In her free time, Mary has enjoyed singing in various choral groups and performing in musical theater.

Did this blog spur new ideas for your music program? Share them on Amplify! Interested in reprinting this article? Please review the reprint guidelines.

The National Association for Music Education (NAfME) provides a number of forums for the sharing of information and opinion, including blogs and postings on our website, articles and columns in our magazines and journals, and postings to our Amplify member portal. Unless specifically noted, the views expressed in these media do not necessarily represent the policy or views of the Association, its officers, or its employees.

Catherina Hurlburt, Marketing Communications Manager. November 19, 2019. © National Association for Music Education (NAfME.org)

Published Date

November 19, 2019

Category

- Uncategorized

Copyright

November 19, 2019. © National Association for Music Education (NAfME.org)