/ News Posts / The Musician of the Month Project

Inspiring Students through Engaged Listening

By NAfME Member Adam N. McLean, M.M.Ed.

Somerville (MA) Public Schools

Immediate Past President, Boston Area Kodály Educators

The original version of this article first appeared in the Massachusetts Music Educators Journal and was reprinted in the Michigan Music Educator.

Whether we teach general music or performing ensembles, elementary or secondary school, vocal or instrumental music, music listening is an important part of our curricula. Music listening has many clear benefits, such as hearing musical concepts in action, developing aural acuity, emotionally connecting with powerful music, and building aspirations for future music-making. It is this last aspect that has interested me most in planning my listening selections. The more my students find personal connections with high-quality, professional-level music, the more excited they are about making music themselves. In this way, the musicians who perform the listening selections in my classroom act as musical role models for my students. This has been true at every level at which I have taught, from pre-K through grade 12.

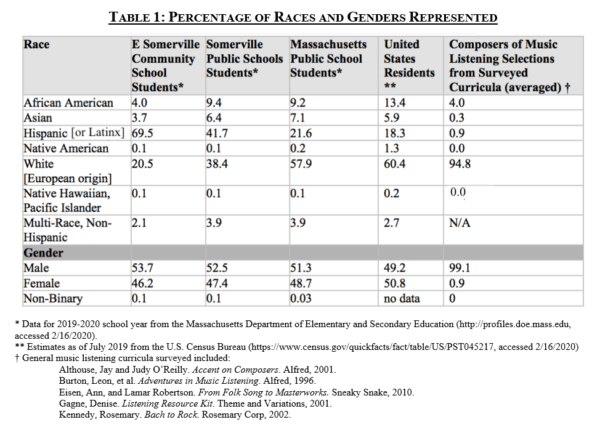

Among Kodály educators, we often hear about presenting “masterworks” and “art music”—those pieces that we lift up as the very best, or music at its finest. However, I have some concerns about the way we represent music at its best. Specifically, I have noticed a pervasive Euro-centrism, elitism, and patriarchy in much of our “masterworks” repertoire. In researching this phenomenon, I did a survey of some popular listening curricula that are designed for general classroom use and compared the representation of races and genders to the demographics of my student body, shown in Table 1.

The listening curricula surveyed clearly demonstrate a strong bias toward European classical music composed by men. There are, of course, exceptions to this in the form of specialized listening curricula that focus on other musical styles or in commercial textbook series that represent a diversity of cultures. While the present article does not explicitly explore these kinds of resources, pre-packaged or scripted curricula that are sold with the promise of “multiculturalism” risk tokenizing the cultures they represent if they do not also ask educators to engage in thoughtful reflection about the cultures present in their own school community. All this notwithstanding, the above data show that mainstream generalized listening curricula are strikingly out of step with the demographics of our schools and of our nation. Indeed, this “standard” listening repertoire seems stuck in mid-20th century Europe.

As a white male music educator steeped and schooled in the European classical tradition, a great deal of this repertoire is in my wheelhouse. I surmise that, given the demographic profile of U.S. music educators, I am not alone in this experience. Additionally, there is a great deal of social pressure exerted by the dominant culture to sanctify this style of music as somehow the highest form of music that was or will ever be created. The bottom line is this: I cannot in good faith lift up “my kind” of music as masterwork to the exclusion of virtually all others when there is so much high-quality music of different origin that has great relevance to my student body. To do so would be, at best, complicit with white supremacy and patriarchy. At worst, it would be an act of oppression.

As Dr. Juanita Johnson-Bailey and Dr. Ming-Yeh Lee write:

Curriculum development is a political decision, in that it involves the inclusion and the exclusion of certain materials. This political decision is often informed by an individual instructor’s positionality. The development of a curriculum that acknowledges the cultural background of diverse learner populations should incorporate various cultural perspectives. A culturally diverse curriculum may broaden students’ knowledge base and understanding as they relate to who they are within their integrated multiple identities and how they relate to others in society. It is also crucial for instructors to select materials that portray various populations’ experiences and materials that center the curriculum around a group’s lived experiences. As instructors we need to ask, how often do the readings for class actually reflect diverse experiences? Are my students’ images or experiences represented in the selected readings? If a group’s images are presented in the readings, do the readings serve to empower the group or to perpetuate stereotypes about the group? We need to be conscious of whose interests are served by the selected curriculum and materials.1

This brings me to some general principles that have guided my thinking about my listening curriculum:

- Just like the folk music repertoire we choose for our student body, there should be some connection between the cultures of our students and the cultures represented in our music listening selections. Students need to see themselves in the curriculum.

- In our multicultural country and global community, it is our moral imperative to teach about music from many different styles with respect for their cultures of origin and those cultures’ particular standards of artistry.

- There should be equal gender representation.

- “If Europe had not existed between the years 1600 and 1900, there would still be music in this world” (Anonymous).

With these principles in mind, my Somerville Public Schools colleagues and I, under the supervision of our Music Director Richard Saunders, have developed an alternative model for music listening, dubbed the “Musician of the Month.” Since implementing the “Musician of the Month” strategy, I can confidently say that it has become one of the most popular and successful elements of my curriculum among students, other staff, and families. The basic features of this model are as follows:

- Each month, a different composer, performer, or ensemble is featured.

- Throughout the year, different styles that exist in the American musical tapestry are explored.

- Musical styles often repeat from year to year, though the featured musicians change.

- There is an equal balance of genders, races, and cultures represented.

- There is a balance between living and deceased musicians presented.

- Special consideration is given to musicians who reach across cultural boundaries and/or who have overcome significant challenges.

- The whole school or district studies the same musician at the same time, with different listening activities modified by grade level.

- Students and families are provided with some means of engaging with the “Musician of the Month” at home (such as through a website or playlist).

- Students review the “Musicians of the Month” at the end of the school year and vote on their favorites.

- Music both in and out of the teacher’s comfort zone is taught.

- Listening activities are meant to involve or inspire active music-making, rather than acting as “music appreciation.”

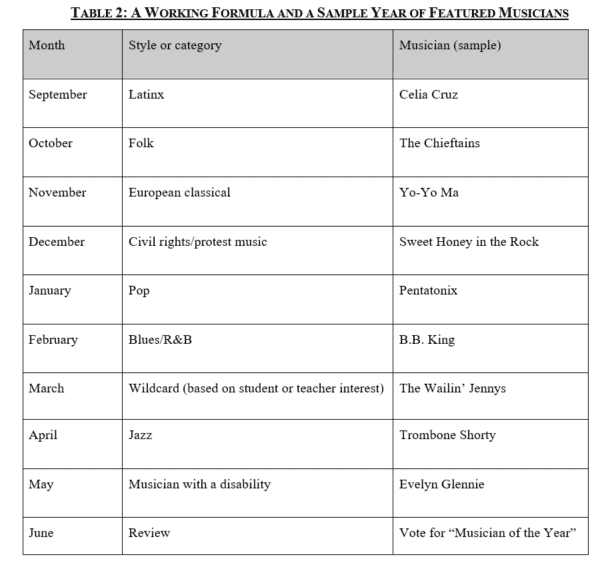

In Somerville, every student in every school, district-wide, studies the same musician at the same time. This builds a culture and excitement around that musician. Siblings, cousins, and friends connect about the musician outside of school. To plan a year of featured musicians, all the general music teachers coordinate via a Google doc, working to balance the styles, genders, and cultures represented. Each of us takes charge of one month to choose a musician, develop materials, and suggest classroom listening activities for different grade levels. This allows each of us to share our expertise, and it also spreads the workload across the whole team. Table 2 shows one possible formula for a sequence of styles and a sample year of featured musicians.

I maintain a website where I include some links to music clips featured in class. I hear all the time that kids are listening at home, and some classroom teachers even play the music for their students during choice time or other appropriate moments. The independent enjoyment of this great music is the biggest indicator to me that the model is effective. As one parent remarked at a school committee meeting, “A few months ago, [my son] came home and told us that he had listened to the most beautiful music that made his body want to dance. He said that the music was performed by ‘The Queen of Salsa’ Celia Cruz. He said his ears had fallen in love that day. So we listened to Celia Cruz day in and day out. A month later, he came home and said that his ears had fallen in love yet again and this time it was with Yo-Yo Ma. He was so moved by the beauty of the cello that he spent the following month begging for cello lessons. With Mr. [McLean’s] guidance, we rented a cello for [my son] and enrolled him in cello lessons.”

The “Musician of the Month” concept has been adopted by many music educators throughout the United States. Some of them have reported remarkable connections with featured musicians that have been facilitated by remote learning platforms. For example, music teachers Michelle McCarten and Ashley Cuthbertson, both based in Virginia, recently hosted a live video chat between their students and alumni of the Fisk Jubilee Singers. Prior to that, Rhiannon Giddens answered their students’ questions via an asynchronous videorecording. Similarly, Yo-Yo Ma created a heartfelt video message for my students in Somerville in November. Several years ago, my middle school chorus students attended a concert by The Wailin’ Jennys (with tickets paid through a DonorsChoose grant), followed by an informal meet-and-greet with the band. All these experiences have made the “Musician of the Month” literally “come alive” for our students.

While the “Musician of the Month” model aspires to be an anti-racist curriculum that challenges the prevailing Euro-centric and white supremacist bias in U.S. education, it is important to note that it is only one facet of Culturally Responsive Teaching in the music classroom. Simply implementing this strategy without addressing other areas of practice does not automatically make one’s classroom “culturally responsive.” As Dr. Yvette Jackson writes, “Cultural responsiveness is not a practice; it’s what informs our practice so we can make better teaching choices for eliciting, engaging, motivating, supporting, and expanding the intellectual capacity of ALL our students.”2

Culturally Responsive Teaching is not a box to check; it is a more general mindset and skill set that must permeate every aspect of our teaching, within which the “Musician of the Month” strategy can be contextualized. This model for music listening presents diverse music to feed the souls of students who come from many different cultures, and it provides musical role models with whom students can identify. If the purpose of music education is to inspire all students to become life-long, active music-makers, the “Musician of the Month” model can be a powerful component of that mission.

For more information, visit: www.musicianofthemonthproject.com

Special thanks to Isun Malekghassemi for her thoughtful feedback and suggestions for this article.

Notes:

- Johnson-Bailey, Juanita and Lee, Ming-Yeh. “Women of Color in the Academy: Where’s Our Authority in the Classroom?” Feminist Teacher, Vol. 15, No. 2 (2005), p. 120.

- Jackson, Yvette. Foreword to Hammond, Zaretta, Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain: Promoting Authentic Engagement and Rigor Among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin, 2015, p. vii.

About the author:

NAfME member Adam McLean is a K–8 general, vocal, and instrumental music teacher at the East Somerville Community School in Somerville, Massachusetts. Inspiring a lifelong love for music-making in elementary and middle-grades students is his professional passion. Adam holds degrees from The Boston Conservatory and Skidmore College, and he earned a Kodály Music Teaching Certificate (Level III) from the Kodály Music Institute of Anna Maria College. Previously, Adam has taught general music in the Boston Public Schools, the Troy (NY) City Schools, and the Cambridge (MA) Public Schools. He presents regularly at local, state, and national music education symposia and has been published in Massachusetts Music Educators Journal and Michigan Music Educator. Adam is the immediate Past President of Boston Area Kodály Educators and is one of the team leaders for the Musician of the Month Project. Adam is also a professional percussionist, a composer, and the proud father of two children (ages 10 and 6).

NAfME member Adam McLean is a K–8 general, vocal, and instrumental music teacher at the East Somerville Community School in Somerville, Massachusetts. Inspiring a lifelong love for music-making in elementary and middle-grades students is his professional passion. Adam holds degrees from The Boston Conservatory and Skidmore College, and he earned a Kodály Music Teaching Certificate (Level III) from the Kodály Music Institute of Anna Maria College. Previously, Adam has taught general music in the Boston Public Schools, the Troy (NY) City Schools, and the Cambridge (MA) Public Schools. He presents regularly at local, state, and national music education symposia and has been published in Massachusetts Music Educators Journal and Michigan Music Educator. Adam is the immediate Past President of Boston Area Kodály Educators and is one of the team leaders for the Musician of the Month Project. Adam is also a professional percussionist, a composer, and the proud father of two children (ages 10 and 6).

Did this blog spur new ideas for your music program? Share them on Amplify! Interested in reprinting this article? Please review the reprint guidelines.

The National Association for Music Education (NAfME) provides a number of forums for the sharing of information and opinion, including blogs and postings on our website, articles and columns in our magazines and journals, and postings to our Amplify member portal. Unless specifically noted, the views expressed in these media do not necessarily represent the policy or views of the Association, its officers, or its employees.

July 30, 2020. © National Association for Music Education (NAfME.org)

Published Date

July 30, 2020

Category

- Culturally Relevant Teaching

- Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Access (DEIA)

- Gender

- Race

- Representation

Copyright

July 30, 2020. © National Association for Music Education (NAfME.org)