/ News Posts / Reevaluating Professional Practice

Reevaluating Professional Practice

Experimenting with the New and Interrogating the Old in Ensemble Music Education

By NAfME Member Brian N. Weidner

As a new band director, I remember having a post-observation conference with my principal. This discussion stood out at the time, because he was persistent in asking, “Why did you do this activity?” and “What was the purpose of that piece of music?” I remember thinking, “Everyone does long tones and interval studies as part of their warmup,” and “Because it’s a march, and we have to play marches!”, followed by “This guy doesn’t understand anything about how bands work!”

Fast forward 20 years. I recently spoke with a colleague who is working on re-envisioning his practices. He recognizes that his students are different from when he started teaching, but he is stuck in a rut. I find myself asking him the same questions: “Why did you do this activity?” and “What was the purpose of that piece of music?” His first response was “Because that’s what I’ve done for the past 25 years,” followed by, “I don’t know why I’ve done that for 25 years.”

Apprenticeship of Observation and Self-Replicating Cycles

Ensemble music education relies heavily on the traditions that have been passed down through generations, leading us to teach as we were taught. Lortie (1977) called this the “apprenticeship of observation.” In this form of incidental learning, we envision our roles as band, choir, and orchestra directors by replicating the experiences we had ourselves, often without conscious intention of why we do a specific activity or how we guide a specific type of learning. This approach to teacher development becomes a self-replicating cycle where we learn in a specific manner, which is reinforced during our undergraduate experiences and leads us to teach in that same way (Weidner, 2019). For me, that model featured director-dominated large ensembles focused on repetitive routines for developing fundamentals and on repertoire development for the next concert at a high-performance level. Because I never encountered them myself, concepts such as musical independence, creativity, comprehensive musicianship, and diverse programming were absent in my initial years as a teacher. I didn’t know what it was that my classroom was missing, but I rather blindly replicated the classrooms that I had experienced.

Importantly, I am not suggesting that my own music teachers were not amazing educators worth emulating. As Fonder (2014) states, “this is not a zero-sum paradigm where something has to decline in order for something to improve” (p. 89). Rather, I suggest we approach the ensemble in a way modeled by Miksza (2013), who advocates for a conscious reconsideration of the ensemble classroom to understand what is working for our students and what needs readjustment.

Reevaluating Our Personal Practices

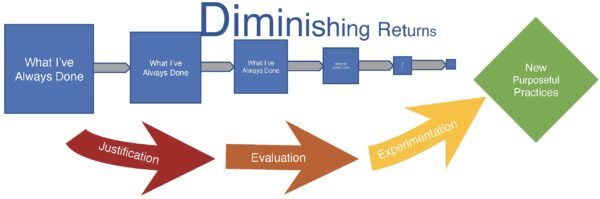

When we blindly use the same strategies without considering their effectiveness, we enter into a space of diminishing returns. It is not a matter that old strategies are not effective, but they may not serve all students in the way they served us. As we search for ways to improve our instruction, the biggest challenge is to honestly evaluate the practices we already use and consider other possibilities. This evaluation starts by first breaking down the rehearsal into its component parts. Video recordings of rehearsals are a great way to go about this. As you watch the video, identify where each different rehearsal activity begins and ends. Each segment should be made up of a single technical exercise, rehearsal approach, or routine element, so you can identify a specific strategy and purpose for each segment.

For each segment, go through the following steps. You do not need to view entire rehearsals all at once, but rather focus on elements that are a regular part of your instruction, such as common warm up exercises and frequently used rehearsal strategies.

Step 1: Justification. Identify what it is that you are trying to accomplish with the activity. What is the concept or skill that students should be developing through this activity?

Step 2: Evaluation. Consider how this particular activity meets its objectives. What allows this instructional approach to be effective at supporting student learning? Importantly, do you use it in a way that maximizes the potential for students to grow?

Step 3: Experimentation. Try out different ways to approach the concept or skill that either modify your original approach or come at it from a completely different angle. How might different sorts of musical learners better understand the objectives of the lesson?

Once we become aware of the self-replicating cycles we are in, we can enter our classrooms fully aware of what is effective and also how to make our classrooms more effective. The goal here is not abandon our successful traditions but rather to sustain them with our eyes wide open by ensuring that we keep what is best practice and augmenting our traditions with new, more effective approaches for our unique students.

References

Fonder, M. (2014). Another perspective: No default or reset necessary—Large ensembles enrich many. Music Educators Journal, 101(2), 89–89.

Lortie, D. (1977). Schoolmaster: A sociological study. University of Chicago Press.

Miksza, P. (2013). The future of music education: Continuing the dialogue about curricular reform. Music Educators Journal, 99(4), 45–50.

Weidner, B. N. (2019). Shrinking the director: Reconceptualizing ensembles in undergraduate music education. New Directions, 4.

About the author:

NAfME member Brian N. Weidner is the assistant professor of instrumental music education at Butler University and holds a Ph.D. in Music Education from Northwestern University with additional degrees in music and education from Olivet Nazarene University, Northern Illinois University, and Illinois State University. Previously, he taught at McHenry (IL) High School for 12 years, serving as its Fine Arts Coordinator and Director of Bands.

NAfME member Brian N. Weidner is the assistant professor of instrumental music education at Butler University and holds a Ph.D. in Music Education from Northwestern University with additional degrees in music and education from Olivet Nazarene University, Northern Illinois University, and Illinois State University. Previously, he taught at McHenry (IL) High School for 12 years, serving as its Fine Arts Coordinator and Director of Bands.

He has published articles in the JRME, MEJ, BCRME, JMTE, Psychology of Music, and regional journals and has presented nationally and internationally. He is also the author of Brass Techniques and Pedagogy which incorporates many of these concepts of critical thinking in beginning instrument instruction. His research focuses on the development of independent musicianship through large music ensembles and processes of disruption in music teacher education.

Did this blog spur new ideas for your music program? Share them on Amplify! Interested in reprinting this article? Please review the reprint guidelines.

The National Association for Music Education (NAfME) provides a number of forums for the sharing of information and opinion, including blogs and postings on our website, articles and columns in our magazines and journals, and postings to our Amplify member portal. Unless specifically noted, the views expressed in these media do not necessarily represent the policy or views of the Association, its officers, or its employees.

June 16, 2022. © National Association for Music Education (NAfME.org)

Published Date

June 16, 2022

Category

- Ensembles

- Music Education Profession

Copyright

June 16, 2022. © National Association for Music Education (NAfME.org)