/ News Posts / Bomba: The Sound of Puerto Rico’s African Heritage

Bomba: The Sound of Puerto Rico’s African Heritage

By NAfME Member Vimari Colón-León

This article appeared in the April 2021 issue of Journal of General Music Education.

Abstract

Bomba is an emblematic Puerto Rican musical genre that emerged 400 years ago from the colonial plantations where West African enslaved people and their descendants worked. It remains one of the most popular forms of folk music on the island and serves as significant evidence of its rich African heritage. This article explores the main components of bomba by making them more accessible to those that have not experienced it from an insider’s perspective. The material presented in this article provides a learning sequence that could take the form of several lessons, or even a curricular unit. Transcriptions of rhythms typically learned aurally are also included.

If you walk through the streets of Old San Juan, a historic district in the capital of Puerto Rico, on the weekend, you will probably see people proudly playing and dancing bomba. This genre is considered one of the oldest musical traditions on the island. It is fascinating to witness it is still thriving after many years, serving as significant evidence of Puerto Rico’s African heritage. In fact, in recent years, bomba has been experiencing a resurgence thanks to the interest of young Puerto Ricans in knowing, understanding, preserving, and enjoying this distinctive part of their culture.

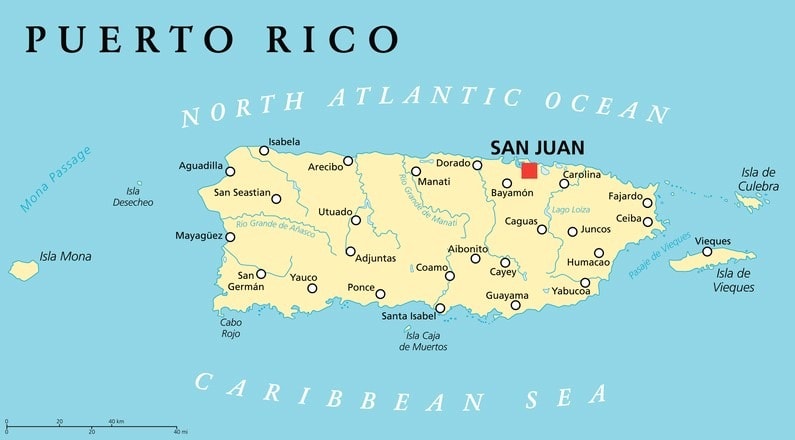

Bomba dates back to the beginning of the Spanish colonial period (1493–1898). The practice was developed by West African enslaved people and their descendants, who worked in sugar plantations along the coast of Puerto Rico (Ferreras, 2005). The towns of Mayagüez, San Juan, Loíza, and Ponce, among others, were the cradle of the various styles that make up this genre. In these areas, cane workers released feelings of sadness, anger, and resistance through fiery drums played in dance gatherings called Bailes de Bomba (Bomba Dances). Enslaved people also used them to celebrate baptisms and marriages, communicate with each other, and plan rebellions (Cartagena, 2004). The roots of this tradition can be traced to the Ashanti people of Ghana, and the etymology of the word “bomba” to the Akan and Bantu languages of Africa (Dufrasne-González, 1994; Vega-Drouet, 1970).

Bomba in General Music Classrooms

This article considers three arguments to support the inclusion of bomba in the general music classroom. First, this musical expression incorporates elements that form part of most general music curricula, such as singing, dancing, drumming, and improvising. These components make bomba an engaging tool for introducing students to important music concepts, develop critical thinking and creativity, and expand their aural experiences (Blair & Kondo, 2008; Fung, 1995). Second, music is at the heart of Puerto Rican culture. Bomba remains one of the most popular forms of folk music on the island, and many cultural events highlight this genre for entertainment. By studying bomba, students get a glimpse into the life and traditions of this country, which positions it as a powerful source for developing intercultural understanding. Last, this musical art allows teachers to practice diversity, equity, and inclusion by providing musical experiences that are culturally responsive (Lind & McKoy, 2016). There has been an unprecedented migration from residents of the Caribbean island of Puerto Rico to the mainland United States during the past 10 years. This trend increased recently in part to the catastrophic effects of Hurricane Maria in September 2017. Federal data suggest that after the impact of this hurricane, people moved from Puerto Rico to every state in the United States (Sutter & Hernandez, 2018).

Initial Analysis

The main principles of ethnomusicology can be used as a framework to explore music from other cultures in the general music classroom. Ethnomusicology examines the relationship between music and culture (Merriam, 1960) and, consequently, contributes a more holistic view of multicultural music education practices. An examination of the bomba tradition through this lens could help teachers understand the musical aesthetics, behaviors, and cultural values associated with it (Table 1). This type of analysis will ensure that the music expression’s authenticity is preserved and will provide different pedagogical angles to approach the learning experience (Sarrazin, 2016).

Table 1. Analysis of the Primary Components of the Puerto Rican Bomba (Ferreras, 2005; Peña-Aguayo, 2015)

| Pedagogies | · Aural

· Call and Response · Traditional model of apprenticeship |

|

Musical Aesthetics |

· Multilayered rhythms in simple and compound meters · Simple chant-like melodies in major or minor keys sang in unisons, parallel octaves, and occasional consonant harmonies. · Lyrics are mostly in Spanish but often feature words or expressions borrowed from former African languages and Caribbean dialects. · Songs often include place names, names of styles, and names of individual persons within the local culture.

|

| Values/Beliefs | · Music and dance are used to express the experience of slavery and social marginalization.

· Music is also a form of entertainment and a vehicle for creating community and identity. · Dance and music are highly integrated. · Improvisation and creativity are highly valued.

|

| Behaviors | · Playful competition between a dancer and a lead drummer

· Participatory music-making · Lead singers play the maracas and mark the length of the song.

|

Call and Response

Call and response is a fundamental ingredient of bomba. Musical performances typically start with a soloist called the laina, singing a phrase to which a group of singers responds. This chorus is supported by musicians that provide different rhythmic patterns with percussion instruments. The song Tócame la Bomba (Play Me the Bomba) popularized by Félix Alduén can be used to showcase this concept and introduce the genre. After listening to the song, students can be invited to comment on the singers’ interaction and overall structure. After, teachers can briefly describe the lyrics’ meaning and encourage students to echo them singing the response. This bomba was selected because its simplicity makes it appropriate for students of different levels and ages. Starting the experience by providing a step-by-step pronunciation guide of the lyrics should be avoided. The importance of learning bomba music by rote can be emphasized by allowing students to experience the song as a whole, just as if it was in their native language. After several repetitions, specific words or phrases can be clarified (Mills, 2009). A full transcription of the lyrics and the chorus’ melody was included in the Supplemental Material.

Chorus/Response

Tócame la bomba, tócamela bien (Play me the bomba, play it to me well)

Toe-kah-may lah bom-bah, toe-kah-may-lah bee-en

Tócamela la bomba, la de Mayagüez (Play me the bomba, the one from Mayagüez)

Toe-kah-may lah bom-bah, lah day Ma-ya-gooez

Mayaguez is a town on the west coast of Puerto Rico. It was one of the places where bomba was born and, subsequently, is often mentioned in songs. Féliz Alduén (1926–2003) is considered one of the most important contemporary exponents of this town’s bomba.

Three-Part Basic Instrumentation

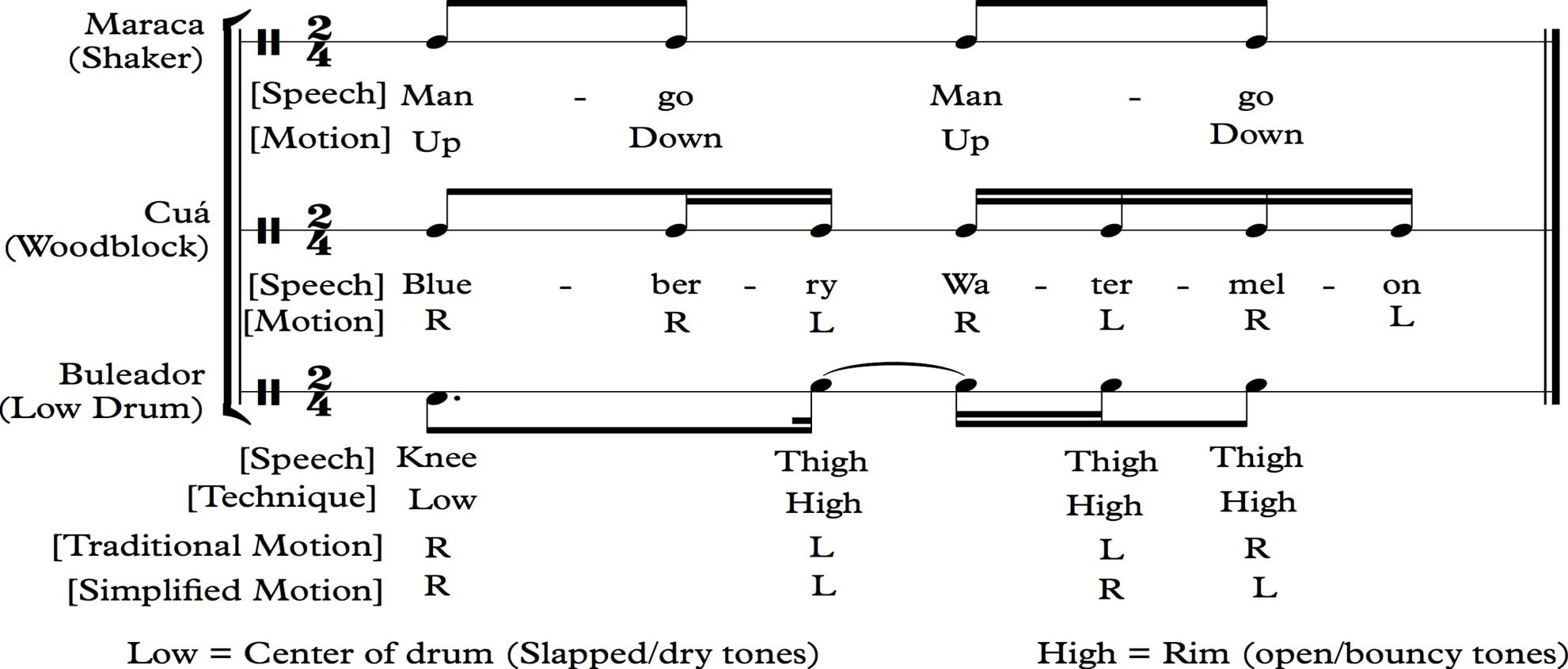

Bomba ensembles are made of a percussion section that includes the following: (a) two or more drums of two different diameters called barriles de bomba (bomba barrels); (b) one large gourd maraca; and (c) one cuá-a stick drum made of a hollow bamboo log (Figure 1). Drums, traditionally made with rum barrels and goatskin, have a hierarchy established by their role in the ensemble. The larger drum is called a buleador and is in charge of keeping the steady beat by playing a foundational rhythm. The high-pitched drum is called a subidor and is responsible for improvising above the large drum. This drum is also used to mark dancers’ movements by producing a type of conversation with each other. The name buleador is used in the north of Puerto Rico, while the same drum is called segundo (second) in the south. The use of alternate names happens again with the subidor drum, also called primo (principal) in the north and tambor primero (first drum) in the south (Cartagena, 2004).

The other two instruments, the cuá and maraca, add additional rhythmic layers that complement the large drum’s rhythm. The cuá is usually placed on a stand and played with two sticks, and in most cases, the lead singer plays the maraca. In a classroom setting, most likely, teachers will not have access to the traditional instruments mentioned here, but others could replicate the sounds they produce. The stick drum could be represented by a woodblock or by hitting a chair with a pair of drumsticks. The maraca rhythms could be performed by any shaker and the bomba barrels by a small and a large drum.

Figure 1. Bomba Instruments.

Note. From left to right: (a) cuá (stick drum); (b) buleador/segundo (large drum); (c) maraca; (d) subidor/primo (high-pitched drum).

Styles of Bomba

It is important to specify that bomba encompasses more than 16 rhythmic styles and that their popularity varies by region. Each rhythm sets the pace of the singing and dance and calls for a different attitude. Some styles, such as sicá, yubá, güembé, belén, corvé, and cunyá, have names that recall their African origin. Others like holandés (from Holland) and leró (the roses) are labeled after European terms and French creole words adopted from neighboring Caribbean islands (Brill, 2017).

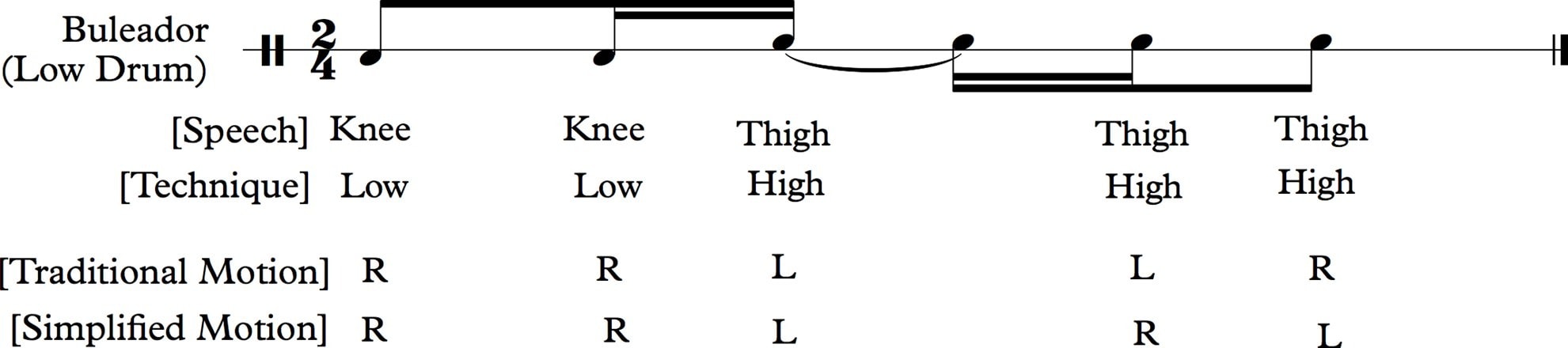

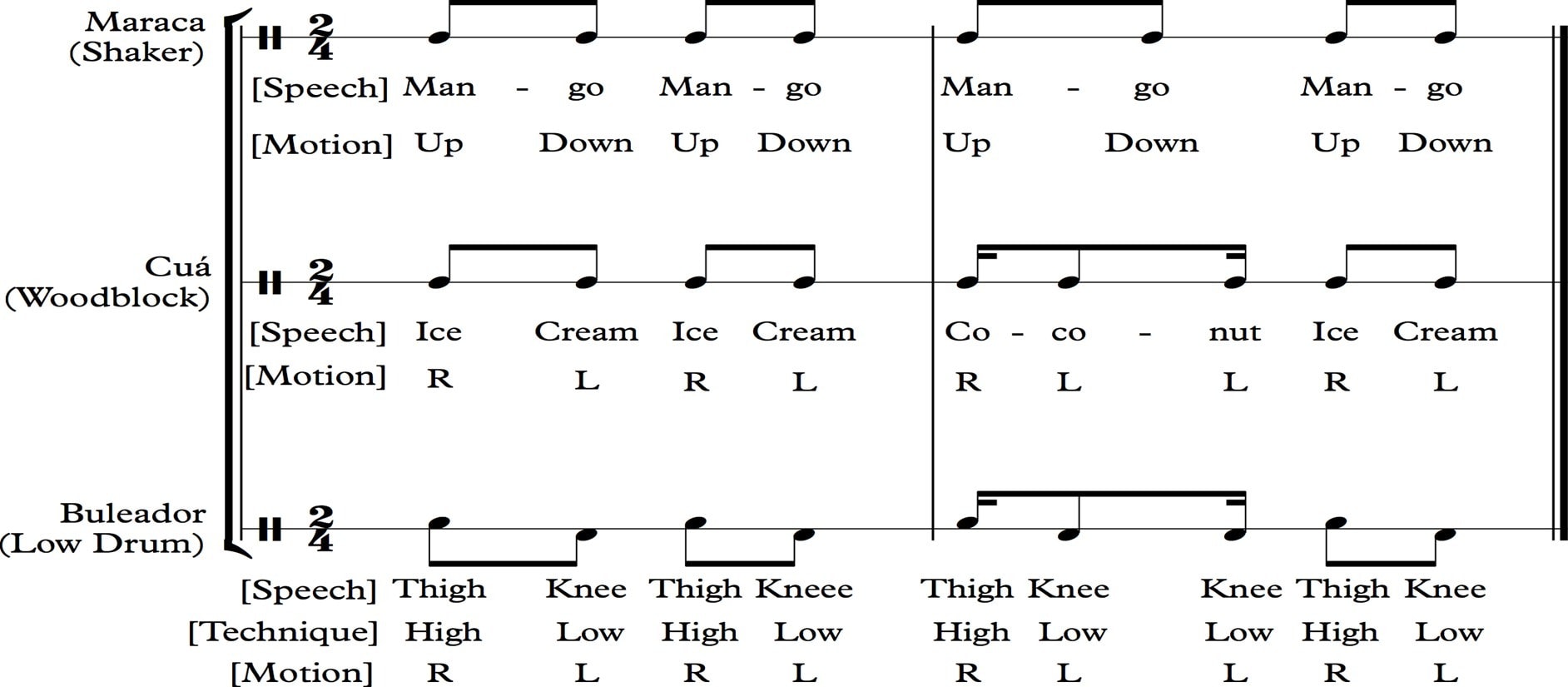

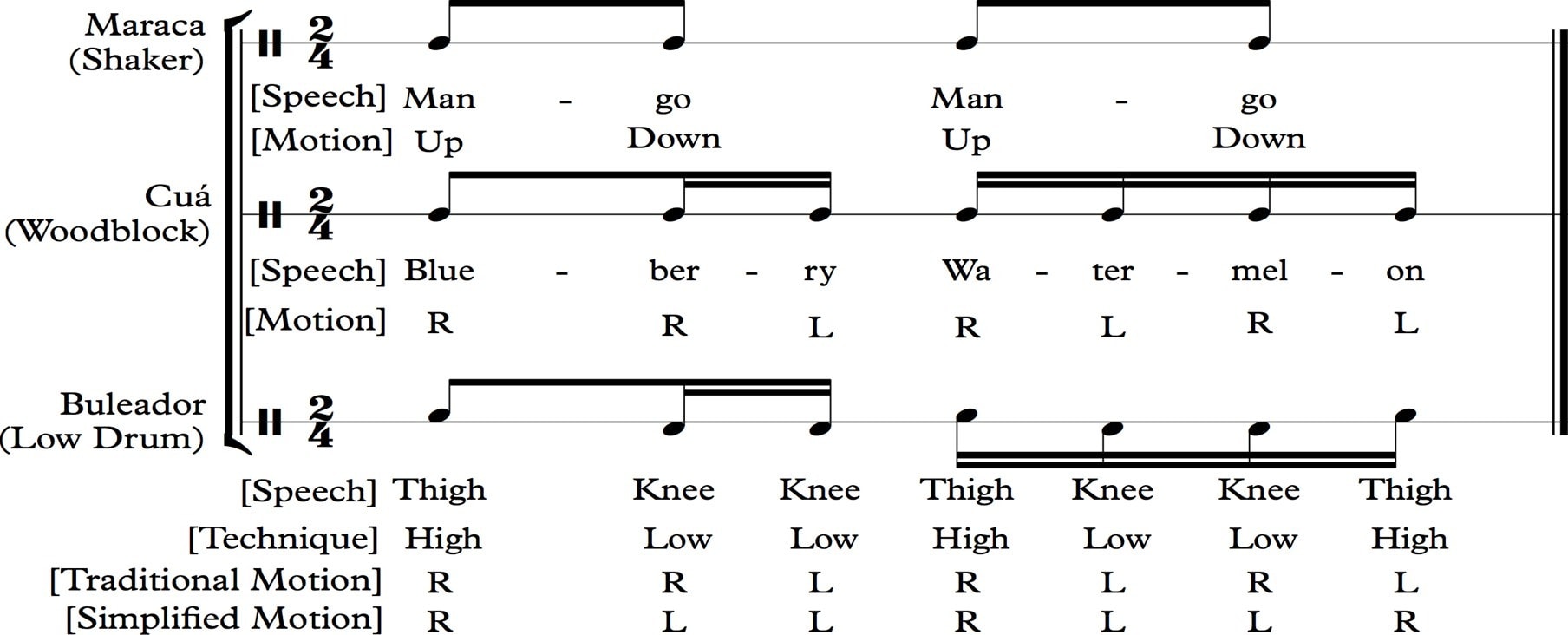

From the myriad of bomba styles, there are three that most people recognize and know. These are the sicá, yubá, and holandés. Sicá is an ideal introductory subgenre because it is the most popular and widespread of the entire tradition (Peña-Aguayo, 2015). To teach students to play this basic style, teachers can start by modeling the large drum’s rhythm using speech and body percussion. The maraca and stick drum rhythms can be introduced once the large drum’s pattern is mastered, and students can keep the steady beat with ease (Figure 2a and b). Subsequently, the group could be divided into three equal parts to combine the layers of sounds. The final step could involve transferring all rhythms to their respective instruments and providing students opportunities to rotate. The high-pitched drum in charge of improvising will be added in the next section.

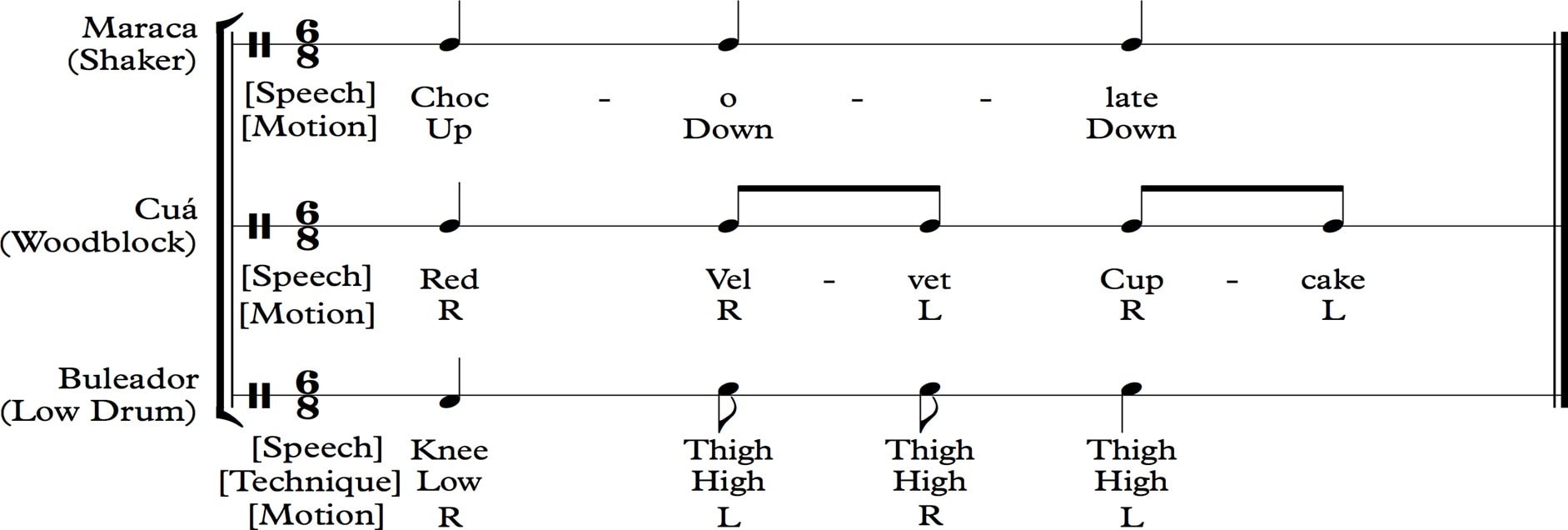

Yubá is the prevailing 6/8 rhythm of bomba. It is played at a moderate tempo and is an essential component of any ensemble’s repertoire (Peña-Aguayo, 2015). The holandés is connected to Dutch slave cultures brought to Puerto Rico from the islands of Curaçao, Aruba, Bonaire, and St. Croix and is characterized by being one of the fastest bomba styles (Ferreras, 2005). The symphonic band piece Tres Ritmos de Bomba (Three Bomba Rhythms) masterfully showcases the rhythms discussed in this section (sicá, yubá, and holandés). It could be used to aurally expose students to the most common bomba styles, including the one they will learn to play (sicá). This work, composed by Angel “Lito” Peña (1921–2002), can be accessed through the Puerto Rico Institute of Culture’s virtual archive, linked at the end of this article. The rhythmic patterns of Yubá (Figure 3) and Holandés (Figure 4) are included below for reference.

Figure 2. (a) Sicá rhythms. (b). Common variation of the rhythm played by the large drum in sicá.

Improvised Bomba Steps

Dancing is another of the central features of bomba. As a song unfolds, dancers break off from the group and step into the drums’ space to challenge the high-pitched drum player to mark their dance moves. The most important terms associated with these practices are paseo and piquetes. Paseo (promenade) refers to the primary dancing step that corresponds to the ensemble’s ostinato rhythm, without calling for improvised beats from the high-pitched drum. It is used when a dancer is about to engage in a dialogue with the lead drummer and waits for its turn. Barton (2004) explains that “this basic step consists of a stylized walk, alternating arms with a toe-touch on each step forward.” (p. 76). Piquetes (accents) are the improvised steps produced by moving a long skirt (females) or different body parts (females and males).

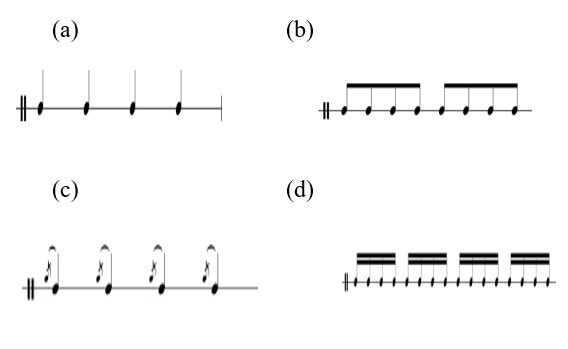

The idea of having to create spontaneous movements and rhythms can be challenging, but some steps could be taken to help students find their creative potential. To prepare them well for this, teachers can start by showing videos of bomba dancers. Later, students can be asked to comment on the dance steps and compare how the interaction between dancer and drummer resembles other types of dances. Teachers could then model the basic promenade step and provide examples of improvised movements (access the videos included in the suggested resources for reference). When students feel comfortable, they could be invited to create other spontaneous steps while using scarves to mirror the skirt’s action. It is important to emphasize that all contributions will be welcomed and celebrated. As the group takes turns to dance, the high-pitched drum’s role could be demonstrated by drumming or clapping patterns that resemble the improvised movements (Scheff et al., 2010). The following patterns (Figure 5a–d) could be used as examples:

Eventually, students could be given turns to take the part of the dancer and the high-pitched drum. While this happens, some could be tasked with playing the sicá rhythm learned previously. Teachers should explain that the high-pitched drum is always in charge of improvising and that this role should be maintained even when there are no dancers on the floor.

Figure 5. (a) Example 1. (b) Example 2. (c) Example 3. (d) Example 4.

Song Structure

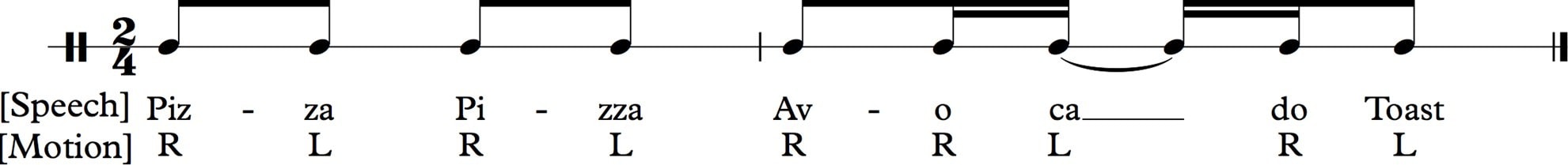

All the steps discussed so far should prepare students to perform bomba with all its traditional components. To keep progressing, teachers could retake the song Tócame la bomba to combine all the elements. This song was recorded by Felix Alduén using a style known as cuembé or güembé (Figure 6). Those interested in challenging their students further could teach them this new pattern. If students are not ready for it, they could also perform it with the sicá rhythm previously learned. Transitioning to this new style should not be difficult because the large drum’s pattern is the only line that changes.

To perform the entire song, teachers should decide the general structure that they will use. The most traditional option would be to start with the lead singer’s call, echoed by the ensemble. Two other options could be to layer the sounds by starting each instrument separately or to begin with the drummers playing a short introduction. In practice, these introductions are called cortes (breaks) or llamadas (calls). Figure 7 provides an example of a possible break.

The final step would be to do a series of call and response interactions over the rhythmic ostinato. After several rounds, options include opening the space for dancers to take turns improvising. Teachers can explain that dancers typically greet the high-pitched drum player with a head nod when they enter the circle in front of the drum section. To conclude the performance, the ensemble could do one last round of the song’s chorus.

Conclusion

Bomba is one of the most emblematic and enduring genres of the island of Puerto Rico. Its history serves as a reminder of the strength and resilience of its people. Its sounds carry stories that are still relevant and deserve to be told. Bomba ultimately represents Puerto Rico’s rich African heritage—one that should be remembered and affirmed by all. The inclusion of this genre and the experiences that it involves enrich the general music curriculum and provide opportunities to learn about cultures that might otherwise not be represented in the classroom. Introducing diverse musical cultures to students provides great benefits for all (Wong et al., 2016).

This article provides a step-by-step approach to introduce students to the exciting world of bomba. This process starts with an initial analysis, an explanation of the concept of call and response, and its three-part instrumentation. The progression advances with an introduction to the genre’s main substyles, steps for elaborating an improvisation, and the different ways to structure a song. With this material, music teachers are invited to empower students to value the diversity of this country and this world.

Suggested Resources

Lesson Plans

Children’s Books about Bomba

- Ortiz, R. (2019). When Julia danced bomba/ cuando julia bailaba bomba. Pinata Books.

- Tucker, M. (2018). Bomba Puertorriqueña (M. Roman, Illus.). Bombazo Dance Co.

Dancing Examples

- Basic dance step for bombas in simple meters.

- Basic dance step for bombas in compound meters.

- Three ideas for dance improvisations.

- Girl dancing bomba.

- Performance by Alma Moyó (bomba ensemble).

Song “Tócame la Bomba”

Bomba Rhythms

- Sicá rhythm.

- Yubá rhythm.

- Holandés rhythm.

- Cuembé/güembé rhythm.

- (2013). Jorge Vázquez. Cuando la Bomba te Llama, Vol. 1. (album with backing tracks for practice)

Symphonic Band Piece (With Sicá, Yubá, and Holandés Rhythms)

- Tres ritmos de bomba.

Terms and Definitions

- Buleador/segundo = Large drum

- Subidor/primo = High-pitched drum

- Laina = Lead singer in charge of calls

- Cuá = Stick drum made of a hollow bamboo log

- Paseo = Basic dance step that involves alternating arms with a toe-touch on each step forward

- Piquetes = Improvised dance steps that are marked by the high-pitched drum

- Cortes/Llamadas = Several measures of a rhythmic pattern played to start the ostinato of the percussion section

References

Barton, H. (2004). A challenge for Puerto Rican music: How to build a Soberao for Bomba. Centro Journal, 16(1), 68–89.

Blair, D. V., & Kondo, S. (2008). Bridging musical understanding through multicultural musics. Music Educators Journal, 94(5), 50–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/00274321080940050111

Brill, M. (2017). Music of Latin America and the Caribbean (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315167213

Cartagena, J. (2004). When Bomba becomes the national music of the Puerto Rico Nation. Centro Journal, 16(1), 14–35.

Dufrasne-González, J. E. (1994). Puerto Rico también tiene tambó: Recopilación de artículos sobre la plena y la bomba [Puerto Rico also has a drum: Compilation of plena and bomba articles]. Paracumbé.

Ferreras, S. (2005). Solo drumming in the Puerto Rican bomba: An analysis of musical processes and improvisational strategies [Doctoral dissertation]. https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/ubctheses/831/items/1.0092337

Fung, C. (1995). Rationales for teaching world music. Music Educators Journal, 82(1), 36-40. https://doi.org/10.2307/3398884

Lind, V. R., & McKoy, C. L. (2016). Culturally responsive teaching in music education: from understanding to application. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315747279

Merriam, A. (1960). Ethnomusicology discussion and definition of the field. Ethnomusicology, 4(3), 107–114. https://doi.org/10.2307/924498

Mills, L. (2009). ¡Salta conejo! A collection of Latin American Children’s Songs for teachers and parents. n.p. AQ

Peña-Aguayo, J. J. (2015). La bomba puertorriqueña en la cultura musical contemporánea (Puerto Rican bomba in the contemporary musical culture) [Doctoral dissertation]. http://roderic.uv.es/handle/10550/54067

Sarrazin, N. (2016). Music and the child. State University of New York at Genesco.

Scheff, H., Sprague, M., & McGreevy-Nichols, S. (2010). Exploring dance forms and styles: A guide to concert, world, social, and historical dance. Human Kinetics.

Sutter, J. D., & Hernandez, S. (2018, February 21). “Exodus” from Puerto Rico: A visual guide. CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2018/02/21/us/puerto-rico-migration-data-invs/index.html

Vega-Drouet, H. (1970). Historical and ethnological survey on probable African origins of the Puerto Rican bomba, including a description of Santiago Apostol festivities at Loíza Aldea (Order No. 7920645) [Doctoral dissertation, Wesleyan University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Wong, K. Y., Pan, K. C., & Shah, S. M. (2016). General music teachers’ attitudes and practices regarding multicultural music education in Malaysia. Music Education Research, 18(2), 208–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2015.1052383

About the author

NAfME member Vimari Colón-León is an assistant professor at Bridgewater College in Bridgewater, Virginia. Her teaching and research interests include teaching music to special populations, parental involvement, and multicultural music education.

NAfME member Vimari Colón-León is an assistant professor at Bridgewater College in Bridgewater, Virginia. Her teaching and research interests include teaching music to special populations, parental involvement, and multicultural music education.

Did this blog spur new ideas for your music program? Share them on Amplify! Interested in reprinting this article? Please review the reprint guidelines.

The National Association for Music Education (NAfME) provides a number of forums for the sharing of information and opinion, including blogs and postings on our website, articles and columns in our magazines and journals, and postings to our Amplify member portal. Unless specifically noted, the views expressed in these media do not necessarily represent the policy or views of the Association, its officers, or its employees.

Published Date

March 30, 2021

Category

- Culture

- Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Access (DEIA)

- Race

- Representation

Copyright

March 30, 2021. © National Association for Music Education (NAfME.org)