NAfME BLOG

Yay Storytime! Musical Adventures with Children’s Picture Books, Part Three

/ News Posts / Yay Storytime! Musical Adventures with Children’s Picture Books, Part Three

Yay Storytime!

Musical Adventures with Children’s Picture Books, Part Three

By Thomas Amoriello Jr.

NAfME Council for Guitar Education Chair

Music can take you many places, and today with the assistance of authors and artists, we visit Paraguay and Harlem. Since the previous “Music in a Minuet” publications of “Yay Storytime! Musical Adventures with Children’s Picture Books” (Parts One and Two) there has been a continued positive social media reception. I am proud to share that the Illinois Music Education Association‘s state journal reprinted an edited version of the first two parts of this series in its winter 2020 issue. This inspired me to reach out to a few more creators of a valuable resource for music educators.

Authors Susan Hood of Ada’s Violin: The Story of the Recycled Orchestra of Paraguay and Roxane Orgill, author of Jazz Day: The Making of a Famous Photograph, cover topics that will certainly enhance your teaching experience. Many elementary and middle school level music educators find value in reading to students, and these books focus on cultural diversity, historical music figures, social issues, and ingenuity and innovation under dire circumstances. These stories are also interpreted with beautiful artistic illustrations and a monumental moment in photography.

Thank you to Ms. Hood and Ms. Orgill for sharing your knowledge with the NAfME membership.

Along with Jazz Day, jazz and gospel musicians such as Mahalia Jackson, Louis Armstrong, and Ella Fitzgerald have been subjects in your other children’s picture books. Beyond your passion for the genre, did you feel there was a void in the literature that you were hoping to fill?

Roxane Orgill: When I wrote If I Only Had a Horn, about Louis Armstrong, picture-book biographies were relatively new, and there were almost none on music for children. This was the mid-’90s, and a search of the shelves at my then-local library in Hoboken, New Jersey, told me there was a void to fill. I was inspired also by one title, then new, by Chris Raschka called Charlie Parker Played Bebop. He’s an illustrator, and the book had hardly any words, but for me, it sent out sparks. I chose Armstrong for my first subject because he had a compelling childhood story and because I was crazy about his early recordings with the Hot Five and Hot Seven bands. I wanted to capture that music in my text.

“I like the context in which music happens as much as I like the music itself.”

Since then there have been dozens of picture books about musicians, even people I thought unsuitable, like Billie Holiday (because her story and her addiction are inseparable and, in my view, too difficult for young children to comprehend). Books on gospel music remain rare, and that’s a shame. Apart from the music, which captivates people of any color, there is so much African American history in the telling of gospel’s development: the Great Migration, the civil rights movement, artists like Romare Bearden and entrepreneurs like Madame C. J. Walker . . . As you can see, I like the context in which music happens as much as I like the music itself. I mean, Mahalia Jackson knew Martin Luther King, Jr.; he adored her cooking. How cool is that?

In addition to a love for jazz, you played the violin, sung in choirs, analyzed a Chopin Ballade for a master’s degree, and are also studying and playing Baroque recorders. How has music shaped your creativity as an author and vice versa?

Music has always been there; I think of it as a gift I was given. Not that I’m gifted, but that being able to hear and appreciate music is a gift. To play it, or more accurately, to try to play it, is a bonus. When I’m researching a musician or musicians for a possible book, I do a lot listening. I can’t write about someone unless their music knocks my socks off. And then, when I’m starting to write, I listen again—but never while writing. I can’t concentrate with music on. But I have the sounds in my head as I write.

“Music has always been there; I think of it as a gift I was given. Not that I’m gifted, but that being able to hear and appreciate music is a gift.”

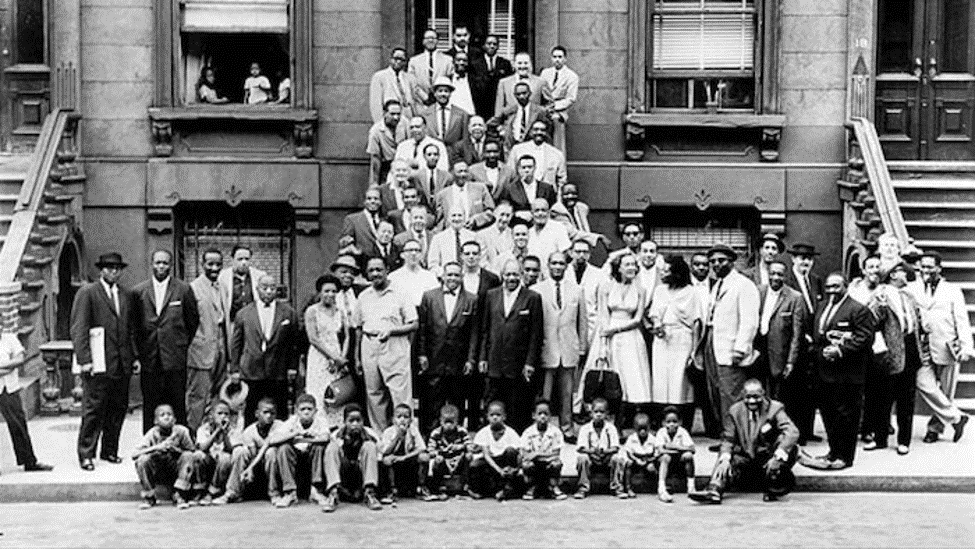

The famous 1958 photograph taken by Esquire Magazine’s Art Kane inspired you to write 21 poems with illustrations by Francis Vallejo. What role did jazz syncopation and rhythm play into your poetry writing?

Relating to your question above, I listened to the music of many of the people in the photograph. I wanted to know the sounds being heard in jazz clubs in 1958. If you hear syncopation and other rhythms in the poems, then that’s probably why.

At one point, someone suggested I write a poem about each of the 57 musicians in the picture, and I thought, oh no! I knew I didn’t have something interesting to say about each one. Instead I chose a handful whose music and stories made me itch to write a poem—plus a figure who wasn’t at the photo shoot, Duke Ellington. He represents the many musicians, including famous ones like Miles Davis, Billie, Oscar Peterson, and John Coltrane, who weren’t there because they were performing elsewhere.

I hope Jazz Day, besides being about a single event, a photo shoot in Harlem, gives readers a sense of both the music and the culture of the period, and then sends people to a streaming service or CDs to listen.

What type of feedback have you received from your work from the jazz and African American communities? Are any descendants of your works or the photograph aware of your work?

Usually what I hear in the African American community is, “Oh, that photo.” Everybody seems to know it. It is incredible, really, that a photo published in a men’s magazine in 1958 has become part of the culture. But I haven’t heard from descendants. I hope I will.

Do you have any future music-inspired children’s picture books in the works that you care to share?

Yes, I’m back to classical music. A picture book on the pianist Glenn Gould is in progress.

Many of the Illustrations from Jazz Day can be viewed here.

Artist Francis Vallejo discusses illustrating the book.

I believe it is wonderful and useful that you created a 9-page curriculum guide to accompany your book and engage children beyond the initial read. It has all sorts of information, activities, discussion questions, a photo of the kids in the orchestra, and additional resources on the web, including one that shows kids how to create their own musical instruments from recycled materials. Was this your idea or the publisher’s, and have you received positive feedback from this from educators?

Susan Hood: Simon & Schuster hired Myra Zarnowski, a professor in the Department of Elementary and Early Childhood Education at Queens College, CUNY, to write the curriculum guide as it relates to Common Core. The guide is available to download free from my website.

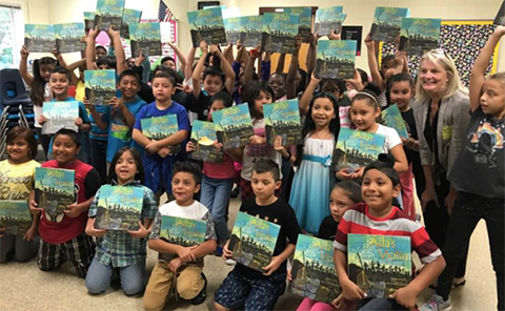

I’ve also heard from teachers about their own genius ideas for using the book. Many, many schools have celebrated Earth Day by asking students to create their own musical instruments from recycled household items. Some even composed songs and treated me to concerts when I visited their schools.

Barbara Wyton, a music teacher at Cider Mill School in Wilton, Connecticut, used the book as a springboard for a six-day, all-school program, tying the book to various curriculum areas: music, Spanish, the science of sound, poverty, environmental concerns, recycling, and more.

Riverdale Country School took advantage of the orchestra’s visit to New York City and invited them to play at the school.

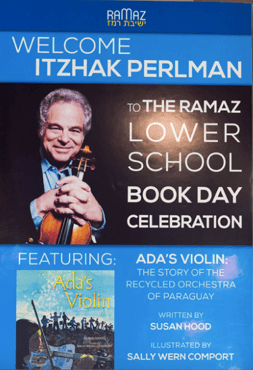

The Ramaz School in New York City read and celebrated the book with the entire Lower School on a special Book Day. Children built their own musical instruments from recycled materials. The school served Paraguayan food, featured Paraguayan dancers, and had a special guest appearance by violinist virtuoso Itzhak Perlman!

You have participated in “Author Visits” to schools in large assembly settings, library groups, and individual classrooms. What types of questions did you receive from children regarding Ada’s Violin?

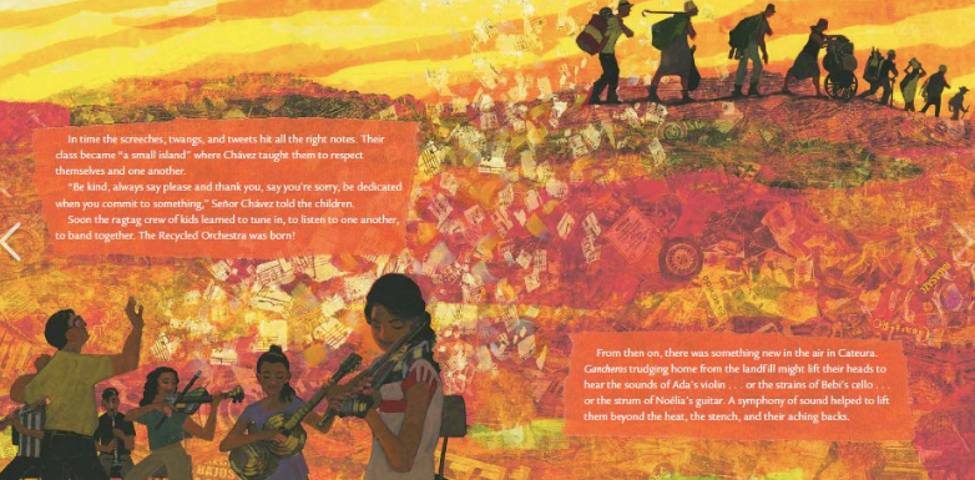

I love doing school visits because the kids ask SO many great questions. They’re always wide-eyed with wonder that these children actually live on a garbage dump in Paraguay and that everything in their lives is recycled from the trash. Students want to know what they eat, where their water comes from, how they get their clothing and toys. My slideshow presentations include photos from the Recycled Orchestra that show the animals they raise for food, their rainwater barrels, their recycled clothing, and the old rusty trucks they play on.

Kids always ask a question I can’t answer. They want to know HOW Cola Gómez makes trash instruments that can play Beethoven, Bach, and Mozart. Nobody knows! He had never seen a violin or heard a violin, but he’s a master carpenter and inventor. With the help of Favio Chávez, the conductor, he tinkered around until he got the sounds just right. Cola is a genius.

“Seeing diversity in children’s books builds both self-esteem and empathy.”

The book is also published in Spanish as EL VIOLÍN DE ADA, La historia de la Orquesta de Instrumentos Reciclados del Paraguay. What were your thoughts regarding children’s literacy and making this available to the Latinx community?

My editor and I thought it was important and only natural that the book be published simultaneously in English and in Spanish. That rarely happens, but we were lucky that Simon and Schuster agreed. As educator Rudine Sims Bishop says, kids need books as mirrors to see themselves and they need books as windows and sliding glass doors into the world. Seeing diversity in children’s books builds both self-esteem and empathy. Recently, the book was published in Japanese. I’d love to see it in many languages to reach as many kids as possible!

You also interviewed Ada Ríos and Favio Chávez for the book, uncovering never-before-heard details of their story. What approach did you take to reinterpret their story into a children’s picture book?

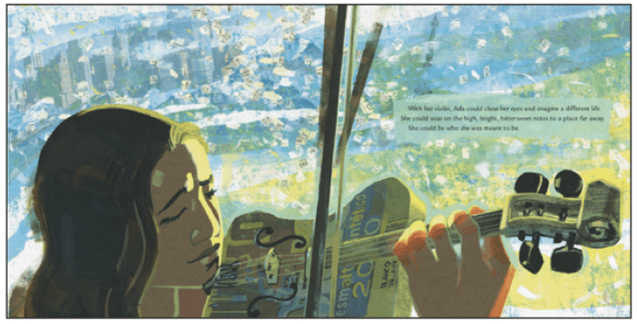

Early on, I decided there were two ways to tell this story: the easy way and the hard way. The easier way would be to use the press reports as background, invent a main character, and write a book “based on a true story.” I lobbied hard for the more difficult approach—nonfiction. Otherwise, I was afraid no one would believe it. Would you believe violins, flutes, and cellos made of paint cans, oil drums, wooden crates, drain pipes, buttons, keys, and forks could play Beethoven, Bach, and Mozart? The story of the orchestra is astounding because it’s all true.

By insisting on nonfiction, I backed myself into a corner. I had to find a child to interview in Paraguay, but I couldn’t afford to travel there. On the landfill, electricity is scarce or non-existent. There are no computers, email, Skype, or even a post office. The orchestra members don’t speak English, and I don’t speak Spanish. I had to hire a Spanish translator, and a bit of luck intervened. It turned out that Favio Chávez did not live on the landfill, but in a nearby city. He did have a computer, email, and Skype, so I did several interviews with him and later with Ada online, getting amazing quotes. My favorite demonstrates Ada’s resilience and optimism. She said she likes to think of each garbage truck arriving at the landfill “as a box of surprises.”

You have donated a portion of the proceeds from the book to the orchestra. What are your own personal thoughts on music education for children, whether living in an impoverished area or rural areas, or in the affluent suburbs?

For me, the Recycled Orchestra is stunning proof of the life-saving power of the arts. When I interviewed Ada, she told me that the violin gave her things she had never had before: something to do, to hope for, to strive toward, to be proud of. It gave her something beautiful in her life.

“For me, the Recycled Orchestra is stunning proof of the life-saving power of the arts.”

Favio Chávez pointed out that music education is a great equalizer: “Playing an instrument is a process. It doesn’t matter if one is rich or poor, ugly, fat, thin, you cannot learn to play an instrument overnight.” And he stressed that kids in the orchestra were learning so much more than music: They were learning to listen to each other, to cooperate, to work as a team.

In their worldwide tours, Chávez said, “Music allowed us to connect with other people. Without even speaking the language, we understand each other.” And people who could never imagine children living on a landfill sat up and took notice. “We take the children to the stage not only as musicians, but we take the children to society’s stage,” said Chávez. “We make them visible.”

Read past articles by Thomas Amoriello Jr.:

- A Cultural Treasure: Interview with Sharon Isbin, Julliard Classical Guitar Program Founder

- The Season’s Greeting’s Guitarist: Trans-Siberian Orchestra’s Al Pitrelli

- Yay Storytime! Musical Adventures with Children’s Picture Books, Part Two

- The Student Teacher in the Guitar Classroom

- Double Trouble: Interview with Innovative Musician Gabriel Guardian

- The Patriotic Guitarist: Master Sergeant Alan Prather of “The President’s Own”

- Interview with Progressive Funk-Rock Guitarist DeWayne “Blackbyrd” McKnight

- Heavy Metal Guitar: Neo-Classical Style

- Heavy Metal Guitar: From Times Square to Netflix and Beyond

- Make a Sound! Interview with Drummer Michael Bland

- What about the Electric Bass?

- An Article for Jazz Educators: Interview with Guitarist Kevin Eubanks

- Hip Hop Empowers: Interview with Harlem-Raised, Boston-Based Hip Hop Artist Billy Dean Thomas

- Heavy Metal Guitar Style: Virtuoso Shred Guitar with Toby Knapp

- Adult Education: Rock Camp

- Musical Adventures with Children’s Picture Books

- Empowering the Musician in Your Classroom

About the author:

Thomas Amoriello Jr. serves as the chair on the NAfME Council for Guitar Education and is also the former Chairperson for the New Jersey Music Education Association (NJMEA). He has had more than fifty guitar and ukulele advocacy articles published in music education journals in Michigan, Ohio, Virginia, Washington, Illinois, Rhode Island, and New Jersey. Tom has taught guitar classes for the Flemington Raritan School District in Flemington, New Jersey, since 2005 and was also an adjunct guitar instructor at Cumberland County College, New Jersey, for five years. He has earned a Master of Music Degree in Classical Guitar Performance from Shenandoah Conservatory and a Bachelor of Arts in Music from Rowan University. His primary teachers have been Alice Artzt, Glenn Caluda, David Crittenden, and Joseph Mayes. He has performed in the master classes of Benjamin Verdery in Maui, Hawaii, and Angelo Gilardino and Luigi Biscaldi in Biella, Italy. During his time on the NJMEA board he has directed guitar festivals and drafted the proposal to approve the first ever NJMEA Honors Guitar Ensemble. Tom is an advocate for class guitar programs in public schools and has been a clinician presenting his “Guitar for the K–12 Music Educator” for the Guitar Foundation of America Festivals in Charleston, South Carolina, and Columbus, Georgia; Lehigh Valley Guitar Festival in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania; Philadelphia Classical Guitar Society Festival, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; NAfME Biennial Conferences in Baltimore and Atlantic City; as well as other state music education conferences in New Jersey, Massachusetts, New York, and Virginia. He has twice been featured on episodes of “Classroom Closeup-NJ,” which aired on New Jersey Public Television. He is the author of the children’s picture books A Journey to Guitarland with Maestro Armadillo & Ukulele Sam Strums in the Sand, both available from Black Rose Writing. He recently has made a heavy metal LP recording with a stellar roster of musicians including former members of Black Sabbath, Whitesnake, Ozzy Osbourne, Yngwie J. Malmsteen’s Rising Force, and Dio that was released on H42 Records of Hamburg, Germany. The record was released on 12-inch vinyl and digital platforms has received favorable reviews in many European rock magazines and appeared on the 2018 Top 15 Metal Albums list by Los Angeles KNAC Radio (Contributor Dr. Metal). His next recording is a 5-track EP called “Dear Dark” which will be released by Ice Fall Records on cassette in March 2020 and features former members of Megadeth, King Diamond, TNT, and Dokken. Visit thomasamoriello.com for more information.

Thomas Amoriello Jr. serves as the chair on the NAfME Council for Guitar Education and is also the former Chairperson for the New Jersey Music Education Association (NJMEA). He has had more than fifty guitar and ukulele advocacy articles published in music education journals in Michigan, Ohio, Virginia, Washington, Illinois, Rhode Island, and New Jersey. Tom has taught guitar classes for the Flemington Raritan School District in Flemington, New Jersey, since 2005 and was also an adjunct guitar instructor at Cumberland County College, New Jersey, for five years. He has earned a Master of Music Degree in Classical Guitar Performance from Shenandoah Conservatory and a Bachelor of Arts in Music from Rowan University. His primary teachers have been Alice Artzt, Glenn Caluda, David Crittenden, and Joseph Mayes. He has performed in the master classes of Benjamin Verdery in Maui, Hawaii, and Angelo Gilardino and Luigi Biscaldi in Biella, Italy. During his time on the NJMEA board he has directed guitar festivals and drafted the proposal to approve the first ever NJMEA Honors Guitar Ensemble. Tom is an advocate for class guitar programs in public schools and has been a clinician presenting his “Guitar for the K–12 Music Educator” for the Guitar Foundation of America Festivals in Charleston, South Carolina, and Columbus, Georgia; Lehigh Valley Guitar Festival in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania; Philadelphia Classical Guitar Society Festival, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; NAfME Biennial Conferences in Baltimore and Atlantic City; as well as other state music education conferences in New Jersey, Massachusetts, New York, and Virginia. He has twice been featured on episodes of “Classroom Closeup-NJ,” which aired on New Jersey Public Television. He is the author of the children’s picture books A Journey to Guitarland with Maestro Armadillo & Ukulele Sam Strums in the Sand, both available from Black Rose Writing. He recently has made a heavy metal LP recording with a stellar roster of musicians including former members of Black Sabbath, Whitesnake, Ozzy Osbourne, Yngwie J. Malmsteen’s Rising Force, and Dio that was released on H42 Records of Hamburg, Germany. The record was released on 12-inch vinyl and digital platforms has received favorable reviews in many European rock magazines and appeared on the 2018 Top 15 Metal Albums list by Los Angeles KNAC Radio (Contributor Dr. Metal). His next recording is a 5-track EP called “Dear Dark” which will be released by Ice Fall Records on cassette in March 2020 and features former members of Megadeth, King Diamond, TNT, and Dokken. Visit thomasamoriello.com for more information.

Interested in reprinting this article? Please review the reprint guidelines.

The National Association for Music Education (NAfME) provides a number of forums for the sharing of information and opinion, including blogs and postings on our website, articles and columns in our magazines and journals, and postings to our Amplify member portal. Unless specifically noted, the views expressed in these media do not necessarily represent the policy or views of the Association, its officers, or its employees.

Catherina Hurlburt, Marketing Communications Manager. February 13, 2020. © National Association for Music Education (NAfME.org)

Published Date

February 13, 2020

Category

- Uncategorized

Copyright

February 13, 2020. © National Association for Music Education (NAfME.org)